Interview Owen Pallett: “I Became Aware Of This Changeable Personality”

While also his most autobiographical work to date, Owen Pallett unveils some of the inner workings of his new record.

Over the years, Owen Pallett has taken on many different forms and many different guises. Whether he be more well known as the powerhouse behind Polaris Prize-winning Final Fantasy, or the right-hand collaborator for Win Butler and Arcade Fire, the string extraordinaire who has lent his talents to the cream of the pop crop, or a recent nominee for an Academy Award, he’s no stranger to diversifying his talent. Now, he’s returned with a fourth solo album, ‘In Conflict’, and he’s finally undertaking the one role he’s managed to miss out until now; himself.

When did the record begin, what was the starting point?

I had been writing lyrics since before ‘Heartland’ even came out and just accumulating a lot of material because I wasn’t really sure what direction I was gonna go with. So, I was doing a lot of experiments writing new fictional songs and also getting more into mining autobiographical material, part of which was inspired by being on tour with the Mountain Goats and seeing how he was able to turn over his life into songs. That was the early stages, but it was really only summer 2011 that I really started working with the band that songs started to slowly get written. Me and the band were writing a lot of songs together, but because it was about getting the band together, it took a little bit longer. Once we were ready to go, in April 2012, we ran the session in Montreal and recorded the bed tracks at Hotel2Tango in Arcade Fire’s studio in Montreal. That was really when things started going. After that, it was just a question of me doing production at home.

When it came to writing lyrics from a more autobiographical place, did you find it more of a challenge?

I didn’t really find it any more or less of a challenge. Writing lyrics for me is always tough, and I think a large part of it is that I - maybe this is a pretentious thing to admit – maybe hold myself to high standards. I throw out a lot of shit, and so it takes me a long time to get stuff that I feel comfortable with saying, ‘Okay, here’s the song.’ At first, there was an emotional moment when I realised that the way I was writing about events that had happened in my life was very different; from myself as an individual behaving in certain ways in periods of my life and how that had nothing to do with how I would treat that situation now, or even the way I would treat the situation last week. I became aware of this very changeable personality, which very quickly became the basis of the record: never this sense of being entirely honourable or entirely responsible or trustworthy.

How does that tie into the idea of this being a record which deals with insanity from a positive, or more “normal” standpoint?

It’s not so much in a positive light, as in an equal state of being. It’s just that whenever I’m in a creative state - whether it’s spending all day writing a piece of new music, or getting hopped up on coffee in the morning and trying to write lyrics - I definitely feel that there’s a connection to some manic state. I feel like my own diagnosed mental ailments kind of feed off those moments. Like a reverse of catharsis - in order for me to make money, I have to allow myself to slip away from a mentally stable environment.

A lot of the songs were meant to be framed as statements of support to my past selves, or other people that might be going through something that I may have gone through. Or, when the topic is of other people or experiences that I may not have had, but I’ve been very close with people who’ve been through that, it’s supposed to be a sort of love song, or statement of support to them.

Each song is its own vignette, its own story?

Yeah, exactly. I was kind of trying to find some nice way to frame it; I was thinking, ‘How can I describe this?’ and I didn’t want it to be ‘diary entries’ because that’s not accurate. They’re semi-fictional, routed in stuff that’s happened but sometimes it’s me, sometimes it’s other people.

How did the name – ‘In Conflict’ – come about?

As I was mentioning, being in these more difficult states, whether it was in the compositional process or in the formative process, I could feel that that and my mindset when I was in a state of stasis or a state of comfort, that these two states were rubbing up against each other. I was feeling very aware of the way that creativity both allowed my relationship to survive – by the creation of work – and also, how it was causing my relationship to be difficult. My boyfriend, whenever I’m being crazy, sings a song that goes ‘Crazy pants!’ at me, and says it’s okay, because the crazy is what makes the money. So, the conflict is really meant to be the duelling states of mind.

And how that affects the other elements of your life?

Exactly. I’ve had therapists and psychiatrists tell me that, often when you get into these mental states, that what you’re trying to do is, you have these synapses that have become worn because they’re firing so often and it becomes the comfortable way that your brain responds to things. The same way that when you stub your toe or see something surprising, you might say, ‘Woah!’ or ‘Oh my god!’, it’s just these natural impulses. In order to break yourself out of these things, you have to really aggressively mentally get these synapses flowing in different directions. That’s the conflict.

In terms of yourself as a narrator: on your previous album ‘Heartland’, you admitted that you were taking on that role from a more outside perspective. However, going into this record, the songs are more autobiographical, so did you feel any different during the writing and recording processes?

Not really. I mean, the whole narrative subject with regards to ‘Heartland’ was… kind of bogus in a way. I mean, I wrote every word, but the fact that you ask that question, I take it as communication that I might have succeeded to some degree, in making it seem as if there were two different people speaking. I mean, it’s always just the same person, just writing words and trying to write them differently, in a way.

You also got to have Brian Eno feature on the record: how was that as an experience, and how did it come about?

Well, he curated a festival in Norway called the Punkt festival in Kristiansand, and he invited me and my band to come play it. We hit it off and he loved the show, thankfully because sometimes we put on some really shitty shows but this one was good. Then, we crossed paths again later in New York, and I was playing a song at an event that he was at; it was actually honouring him. He really liked the song and I asked him if he wanted to sing on it, so we corresponded digitally, I sent him the record, he worked on doing backing vocals, synth and guitar at home, and sent them back to me, then we chose the stuff that we liked the most, and that was it!

You’ve mentioned that when you were writing these songs, and you were using both you own and other people’s stories, that you were using them to act as statements of support. Did you have the audience in mind, also, and what might they might take away from the tracks?

A large influence on this record that made me very aware of the difficulty about communicating about mental illness with people is the wall that exists. That when you make the ‘It gets better’ videos, there’s still the boundary of the Youtube channel. When you’re in a doctor-patient relationship, there’s still the sensation that the doctor is an omnipotent force that is not actually there with you. I really hope that this record seems less like I’m whining about my emotions, because I’m not, but rather just being very up front about this stuff, in a way that hopefully people will see something. I mean, I’ve always made myself very available in an online way, so I always hope that there would be a one-to-one interaction.

Owen Pallett’s new album ‘In Conflict’ is out now via Domino.

“Whenever I’m in a creative state, I definitely feel that there’s a connection to some manic state.”

How does that tie into the idea of this being a record which deals with insanity from a positive, or more “normal” standpoint?

It’s not so much in a positive light, as in an equal state of being. It’s just that whenever I’m in a creative state - whether it’s spending all day writing a piece of new music, or getting hopped up on coffee in the morning and trying to write lyrics - I definitely feel that there’s a connection to some manic state. I feel like my own diagnosed mental ailments kind of feed off those moments. Like a reverse of catharsis - in order for me to make money, I have to allow myself to slip away from a mentally stable environment.

A lot of the songs were meant to be framed as statements of support to my past selves, or other people that might be going through something that I may have gone through. Or, when the topic is of other people or experiences that I may not have had, but I’ve been very close with people who’ve been through that, it’s supposed to be a sort of love song, or statement of support to them.

Each song is its own vignette, its own story?

Yeah, exactly. I was kind of trying to find some nice way to frame it; I was thinking, ‘How can I describe this?’ and I didn’t want it to be ‘diary entries’ because that’s not accurate. They’re semi-fictional, routed in stuff that’s happened but sometimes it’s me, sometimes it’s other people.

How did the name – ‘In Conflict’ – come about?

As I was mentioning, being in these more difficult states, whether it was in the compositional process or in the formative process, I could feel that that and my mindset when I was in a state of stasis or a state of comfort, that these two states were rubbing up against each other. I was feeling very aware of the way that creativity both allowed my relationship to survive – by the creation of work – and also, how it was causing my relationship to be difficult. My boyfriend, whenever I’m being crazy, sings a song that goes ‘Crazy pants!’ at me, and says it’s okay, because the crazy is what makes the money. So, the conflict is really meant to be the duelling states of mind.

And how that affects the other elements of your life?

Exactly. I’ve had therapists and psychiatrists tell me that, often when you get into these mental states, that what you’re trying to do is, you have these synapses that have become worn because they’re firing so often and it becomes the comfortable way that your brain responds to things. The same way that when you stub your toe or see something surprising, you might say, ‘Woah!’ or ‘Oh my god!’, it’s just these natural impulses. In order to break yourself out of these things, you have to really aggressively mentally get these synapses flowing in different directions. That’s the conflict.

“A large influence on this record that made me very aware of the difficulty about communicating about mental illness with people is the wall that exists.”

In terms of yourself as a narrator: on your previous album ‘Heartland’, you admitted that you were taking on that role from a more outside perspective. However, going into this record, the songs are more autobiographical, so did you feel any different during the writing and recording processes?

Not really. I mean, the whole narrative subject with regards to ‘Heartland’ was… kind of bogus in a way. I mean, I wrote every word, but the fact that you ask that question, I take it as communication that I might have succeeded to some degree, in making it seem as if there were two different people speaking. I mean, it’s always just the same person, just writing words and trying to write them differently, in a way.

You also got to have Brian Eno feature on the record: how was that as an experience, and how did it come about?

Well, he curated a festival in Norway called the Punkt festival in Kristiansand, and he invited me and my band to come play it. We hit it off and he loved the show, thankfully because sometimes we put on some really shitty shows but this one was good. Then, we crossed paths again later in New York, and I was playing a song at an event that he was at; it was actually honouring him. He really liked the song and I asked him if he wanted to sing on it, so we corresponded digitally, I sent him the record, he worked on doing backing vocals, synth and guitar at home, and sent them back to me, then we chose the stuff that we liked the most, and that was it!

You’ve mentioned that when you were writing these songs, and you were using both you own and other people’s stories, that you were using them to act as statements of support. Did you have the audience in mind, also, and what might they might take away from the tracks?

A large influence on this record that made me very aware of the difficulty about communicating about mental illness with people is the wall that exists. That when you make the ‘It gets better’ videos, there’s still the boundary of the Youtube channel. When you’re in a doctor-patient relationship, there’s still the sensation that the doctor is an omnipotent force that is not actually there with you. I really hope that this record seems less like I’m whining about my emotions, because I’m not, but rather just being very up front about this stuff, in a way that hopefully people will see something. I mean, I’ve always made myself very available in an online way, so I always hope that there would be a one-to-one interaction.

Owen Pallett’s new album ‘In Conflict’ is out now via Domino.

Read More

Owen Pallett announces Autumn tour dates

Also: Listen to a new remix of ‘Song For Five & Six’ by Spinn and the late DJ Rashad.

23rd June 2014, 12:00am

Owen Pallett - In Conflict

3 Stars

An undeniably strong album, in which existing fans will find much to love.

12th May 2014, 8:27am

Watch: Owen Pallett Unveils ‘Song For Five & Six’ Video

Video stars students at the National Ballet of Canada.

22nd April 2014, 2:34pm

Listen: Daphni & Owen Pallett Collaborate On ‘Julia/Tiberius’ Split Single

Owen Pallett and Dan Snaith (aka Caribou) collaborate for the first time on this split release.

14th April 2014, 2:34pm

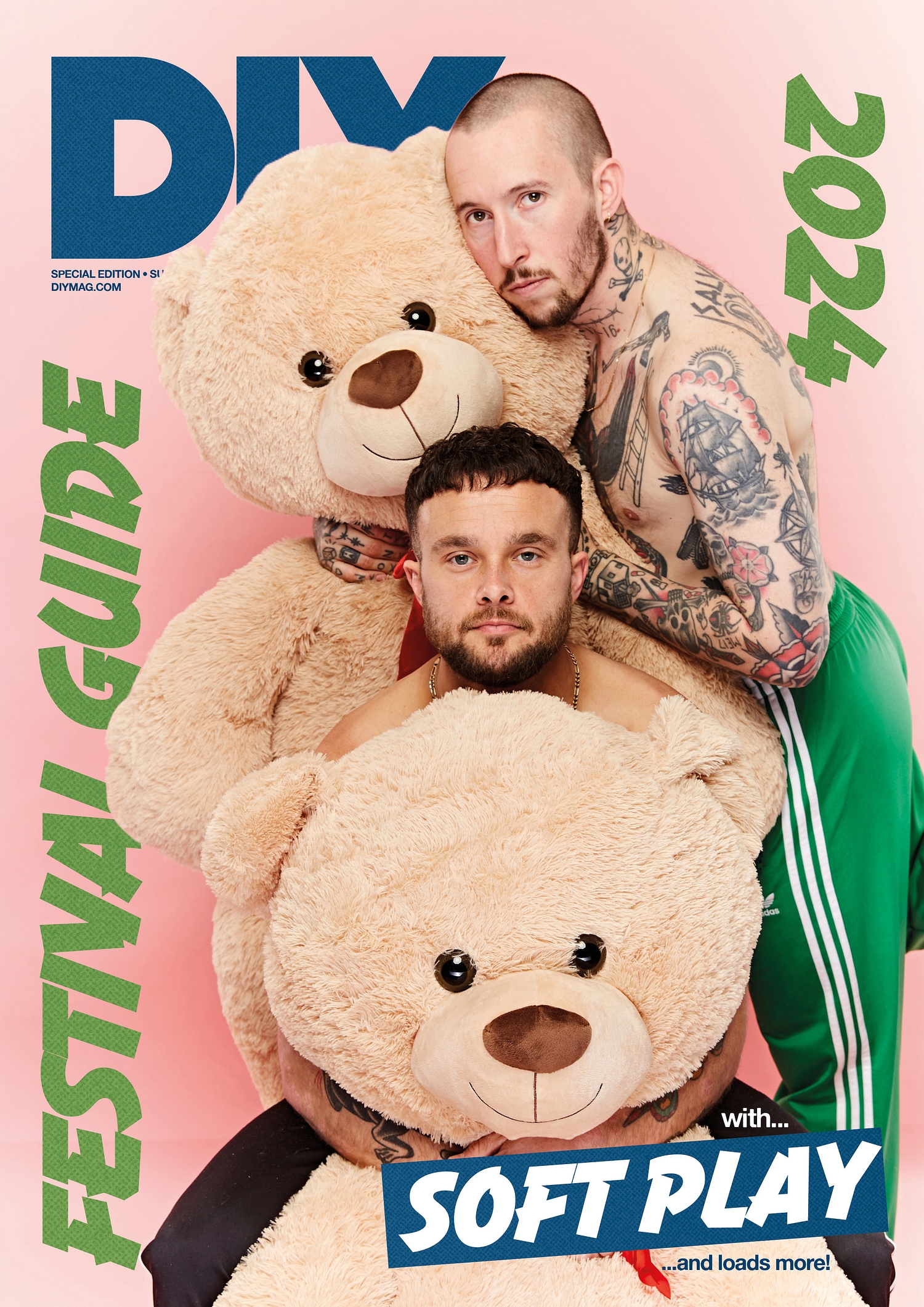

Featuring SOFT PLAY, Corinne Bailey Rae, 86TVs, English Teacher and more!