Neu Tiña: “I’m just hoping to become the pink messiah”

Speedy Wunderground’s first ever album signings, taking pain and turning it into their own positive pink party.

“There’s this bit in a Richard Brautigan book called Sombrero Fallout, where he’s crying into a bin because he and his girlfriend have broken up, and he cries for so long that he loses his perception of time and it feels like he’s been crying into this bin forever. So then he starts creating a world at the bottom of the bin,” relays Joshua Loftin. “There’s a humour in the surrealness of the tragedy.”

It’s an unusual analogy, but in many ways Tiña - the south London outfit fronted by Josh, and completed by bassist Adam Cartwright, guitarist Ollie Lester, keyboardist Calum Armstrong and drummer George Rhys Davies - are very much the sound of a surreal, magical world plucked out the bottom of a tear-filled bin. On one side, they’re a riot of pink and playfulness - a group whose leader is rarely seen on stage without his trusty cowboy hat, and whose aim, they claim, is to create a “pink party” for listeners to lose themselves in. On the other, they’re a band explicitly born out of a breakdown, with tracks that regularly deal in images of suicide and despair, and a just-released LP called - somewhat ironically - ‘Positive Mental Health Music’.

The reality as we meet them at Speedy Wunderground’s second studio HQ in Streatham - the place where they recently recorded said album at the behest of label boss Dan Carey, who picked the group to become the singles label’s first full-length release - is that they are, like many people, a combination of both. Tiña deal in the confusing grey areas between pleasure and pain, where horror and humour are “two sides of the same coin”, and where wonky, psych-flecked pop is as good a vehicle to get out your woes as any. “That film Manchester by the Sea as well,” picks up Adam, “it’s so dark, but then there’s a bit where they keep dropping the gurney and it’s such a weird moment. His wife has almost been killed and then there’s this random comedy bit in there, but it’s not really a juxtaposition. In the most tragic moments, the most stupid, ridiculous things can happen. I don’t think it’s our job as a band to separate those things out when they seem to go hand in hand more often than not.”

“Everyone’s taken on this unspoken, wonky, playful, feminine aesthetic that then bounces off each other.”

— Josh Loftin

Before Tiña, Josh and Adam used to play as members of Bat-Bike - a grottier affair, who hung around in musical circles frequented by Fat White Family, Meatraffle and the like. By the end of the band, Josh had “kind of given up playing guitar” (“Bat-Bike wasn’t doing much, I’d broken up with my girlfriend and wasn’t feeling happy about much,” he says). Yet when he found himself drawn to the instrument again, playing purely as a means of misery-baiting catharsis which then slowly turned into proper songs, the world that he wanted to build around him emerged as a very different one. “The band was called Tina without the ‘ñ’ and we had the pink and there was definitely more of a push towards femininity,” recalls Adam of their genesis. “A lot of that [old] scene may have been commenting on masculinity, but it still very much embodied the stereotypes of masculinity. When the band were forming, we were trying to push more into a feminine place.”

“I remember seeing an image of this Japanese guy wearing a very American Western-looking outfit - this pink suit and a black leather hat - and I thought it looked really bad in a really great way,” continues Josh. “And then as we rehearsed it adapted and everyone took on this unspoken, wonky, playful, feminine aesthetic that then bounces off each other. That’s what the pink party thing is too, because a party is everyone together, right? It’s not someone leading the party and then other people following the party leader; everyone’s having a party together. I like that.”

On ‘Positive Mental Health Music’, that sense of togetherness and a warm, safe space comes through in spades: like if The Brian Jonestown Massacre dealt in cuddles and kindness instead of firing all their bandmates and getting in a strop, Tiña’s party is one that pulls from the alternative music world’s more idiosyncratic corners (Aussie singer Kirin J Callinan is cited as a particular favourite) and then turns it into “a really shit children’s birthday for adults”. The hope, they say, is to take the trauma that comes part and parcel with this thing we call life, and find ways to tame it as best they can.

“It’s not like it solves it; it’s not like, job done, I’m not heartbroken anymore. But it’s good to have a positive thing that can occupy that same mental space. You feel shit, but you also have a good song that’s come out of it,” explains Adam. “If you turn it into a song that’s true then you put ownership on it, because it feels like you’ve taken a bit of control of your life and feelings,” nods Josh.

“I’m just hoping to become the pink messiah.”

Read More

Tiña share video for ‘Closest Shave’

The track is taken from last year’s ‘Positive Mental Health Music’.

28th September 2021, 12:00am

Goat Girl, The Orielles, Do Nothing, Connie Constance & more to play DIY’s Big Bank Holiday Weekender

That's right - with a little help from Marshall, we're hosting a big ol' (socially distanced) gig later this month and you're all invited!

5th May 2021, 12:00am

Sorry, Goat Girl, Connie Constance and more set Hackney ablaze at DIY’s Big Bank Holiday Weekender

Live music - oh how we’ve missed you.

6th March 2021, 12:00am

Tiña - Positive Mental Health Music

3-5 Stars

A debut record that quietly paves the way for modern psychedelic pop.

5th November 2020, 7:57am

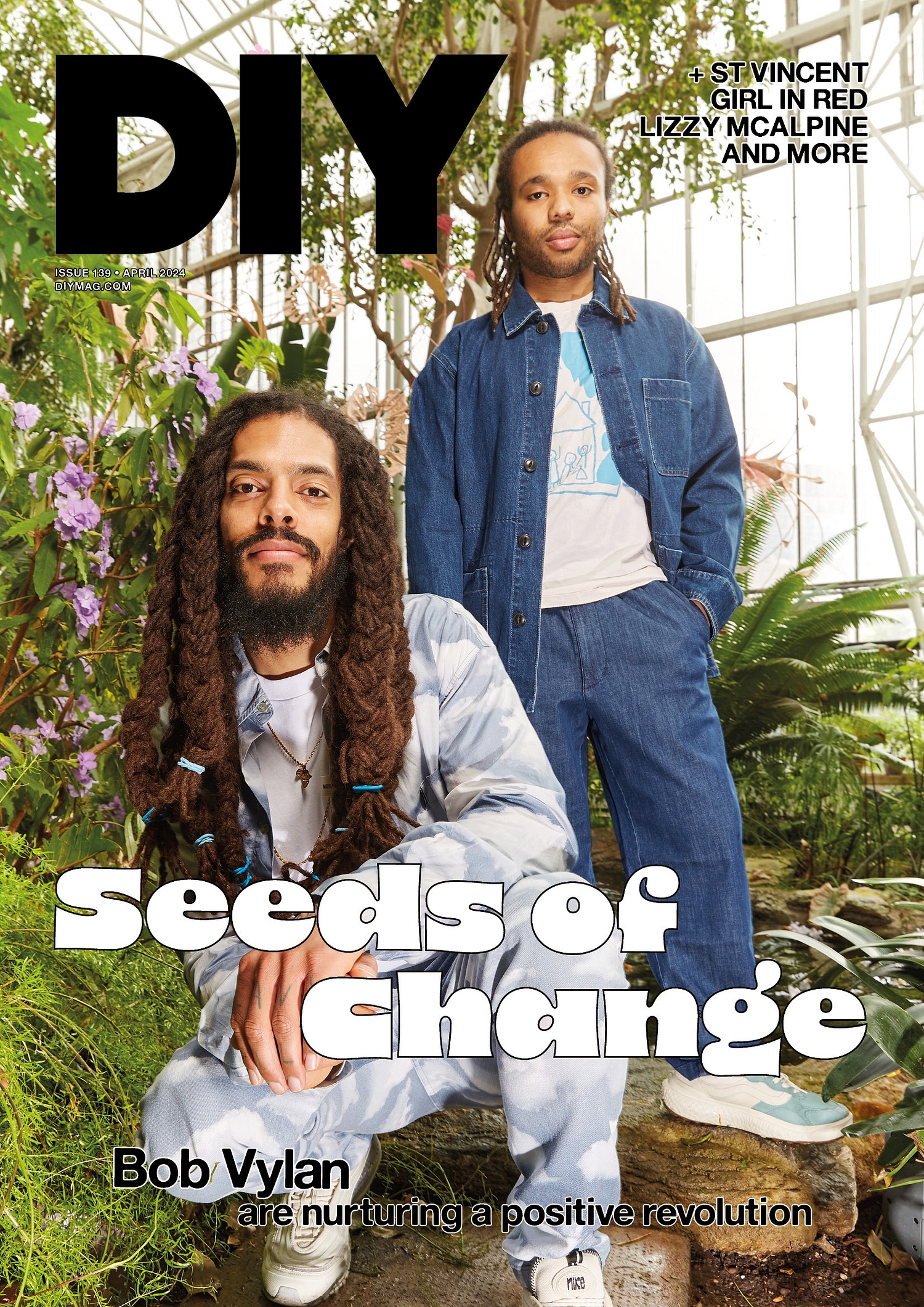

With Bob Vylan, St Vincent, girl in red, Lizzy McAlpine and more.