Live Review

Ben & Jerry’s Sundae 2009

Picnic mats are in bountiful supply, each day ends at eight, and the “insufferable ordeal” of camping is completely out of the question.

is widely credited, amongst those aware of its existence, as the festival to which you can bring your mother along (didn’t bring my mother) – picnic mats are in bountiful supply, each day ends at eight, and the “insufferable ordeal” of camping is completely out of the question. The wholesome, familiar aesthetic is perpetuated further by the sheer wealth of attractions, and collateral spectacles, to be sampled: the helter skelter casts an inviting shadow over the carousel, which is found opposite the coconut shy and the somewhat less sanitary toe wrestling stage, everything imbued with the sumptuous afterthought of free ice cream. The weekend, in previous years, has admittedly engaged consistently stale lineups, as if providing music simply to satisfy the contemporary moniker of “festival”. Nonetheless, the acts arranged for this latest edition, while not unequivocally delectable, are witness to the fact that, beyond the gulf of muddied children and discarded falafel wraps, lies a music stage that warrants a degree of attention.

Since the festival fashions itself in the image and unabated amusement of a “family fete”, it is never curious to find that most of the bands, on Saturday’s bill at the least, are rather ‘safe’ and inoffensive. Tommy Reilly, for instance, is particularly fitting. The Orange Unsigned Act victor, exhibiting tracks from imminent debut album ‘Words On The Floor’, exudes a tangibly versed confidence, a far cry from his jaded incidence on the show. The relatively short set is, nonetheless, riddled with the sheepish charm for which the 19-year old has become famed. The precedence is requisitioned by solitary, agitated acoustic guitar throughout, with Reilly’s own obtuse, yet pragmatic vocal curve. An amalgam, however, of a scarce early afternoon crowd and the permeating notion that Reilly, as a songwriter, has not yet roused himself from an analogue thematic range renders his efforts somewhat inconsequential. Though markedly lustful, and commanding a larger gathering, Marina and the Diamonds are no more successful in pervading the musty complacence with which many approach the stage at this hour. The set is navigated with a particularly obstinate fervour, where frontwoman Marina Diamond commands a marauding, inexorably animated stage presence, in line with her own hostile vocal persuasion. Encumbered bass and metallic, brittle percussion, meanwhile, abundant in the haunting ‘Shampain Sleeper’, complete the hilt of archaic nihilism, in blunt contrast to the embrace of the sunshine. A suitably binary cover of Late Of The Pier favourite ‘Space and the Woods’ is played, accompanied by an accordingly stuttering light show. The crowd’s painfully fibrous disenchantment and at best fleeting interest, however, prove insurmountable and the band, eventually, relent to the awkward difficulty of the task.

It becomes incrementally apparent that the acts scheduled for the earlier phases of the day are less performing than simply struggling to garner a significant audience. It is a fight that Scottish bards King Creosote almost intend to lose. Their frugal resonance, incidental percussion and lethargic acoustic pace epitomises the rigid serenity imposed on the day at large. As such, the set acquiesces into the static, eternally giddy wayside. The trinket, lavatorial focal points of many of the songs, in addition, appear to accelerate the process. In short, the band is never as arresting as required, presenting a single, vacuous escalade. Fortunately, seminal headliners Super Furry Animals are ample redemption. The final shrapnel of the Britpop era takes the stage in mockingly furtive fashion, only to assume an indefatigably brazen form and resolve. What follows is a set of unmitigated classics, all the while singed with the speculative ambition of the 90’s, denoted by the plentiful autotune and polystyrene synth taunted by more rustic instruments throughout. The band, with no redundant actions, lunge into ‘Rings Around The World’, followed seamlessly by the acrid ‘Juxtaposed with U’ both a testament to Gruff Rhys’ veracious vocal swagger, today brandishing cue cards reading “APPLAUSE!” and “WOAH!”. ‘Mountain’, meanwhile, demonstrates that Dafydd Iuean’s coarse fortress of percussion is as capable of understated, nimble movements as it is chaotic denouements. By the end of this execution of nomadic odysseys, the crowd are finally perturbed into their reactionary selves, no longer incumbent or resigned to idly digesting food.

The notion is carried into Sunday, which brings with it a greater prevalence afforded to the music stage. At the very least, The Brute Chorus attract a greater audience than their Saturday early afternoon counterpart, with a brusque, understated old western aesthetic and an emphasis on imposing beats. Their stage presence is accordingly antagonistic, with inverted, pondering synth startled by predatory percussion and frontman James Steel’s able vocal capacity. Throughout, the bass guitar, saturated with an undoubted blues influence, remains the constant of altruistic melancholy, punctuating the stories of reluctant love, degradation and flint personalities that ensue. The conception is boisterous in the robust, archaic narrative of new song ‘Hercules’, afforded a rusted sheen by cowbells and intricate drum fills. The veiled, considered funk placates the modest crowd by the end of the set.

The palpable tenacity is a trait shared by NME lovechildren Red Light Company, who radiate an instant affinity toward the live performance despite the infantile stage of their careers. In around half an hour, we are exposed to a distinctly ardent brand of augmented indie, characterised by bothersome, consistently negative basslines and a dexterity for insuperable choruses. A sombre, repressed diction is perpetuated by Richard Frenneaux’s contorted vocal curve and the concentration of tumbling percussion, both giving generous weight to the often frenzied culminations to many songs. A complete departure, however, from such impatient fervour is induced with the arrival of Camera Obscura, who assert a blissful resonance, distant from the remainder of the bill. The prevailing sensation throughout is one of articulate frivolity, embossed by nautical guitar and faint, enthused synth and xylophone, retained despite the morbid quality of some songs. Nothing of the luminosity of the tracks on record are lost during this live fare, seen in the impeccable execution of ‘Lloyd, I’m Ready to Be Heartbroken’, where a streamlined, viscose calibre instigates myriad instances of angular dance amongst the ever-accommodating crowd. A musky euphoria associates itself both with the male and female vocal harmonies and the loitering aftertaste of brass, adapted amiably to the live performance. In due course, the Glaswegians brave an initially disconcerting audience and fleeting technical difficulty to purvey a set of patently inimitable persuasion.

As the weather takes an increasingly morose turn, our sensibilities are rendered quite the opposite. Sunday’s new wave headliners The Human League, notwithstanding an embattled 32-year history, maintain a fresh, watertight resolve and energy that defies their age: Phil Oakey and company remain diligent both in the sartorial and instrumental sense. The band’s original equipment and setup are restored in their full ersatz valour, where the predominantly digital arrangement evokes a sound as surgical and as arresting as in their mid-80’s peak. Clockwork electronic percussion flanks tenuous dual keys inclined towards, higher, jubilant notes, all superimposed onto the contemporary predilection of guitar, providing the cardinal riff in a revised rendition of ‘Fascination’. The trio’s stage demeanour is equally vivacious - The Human League are one of very, very few bands that are able to conduct mid-set wardrobe changes with impunity, a fixture that was necessary for their escapist delineation of the ultimately rather moribund 80’s, and one, incidentally, that becomes viable in these sparing modern times. It is such autonomous zeal that typifies the prolonged set, closing with the stellar ‘Don’t You Want Me’ to be heralded as the only band of the weekend to be called for an encore. It is a novel accentuation of the high points of a festival that, while established, has not yet calibrated itself fully towards musical acts, a stance that future iterations, and copious amounts of ice cream, are bound to rectify.

Records, etc at

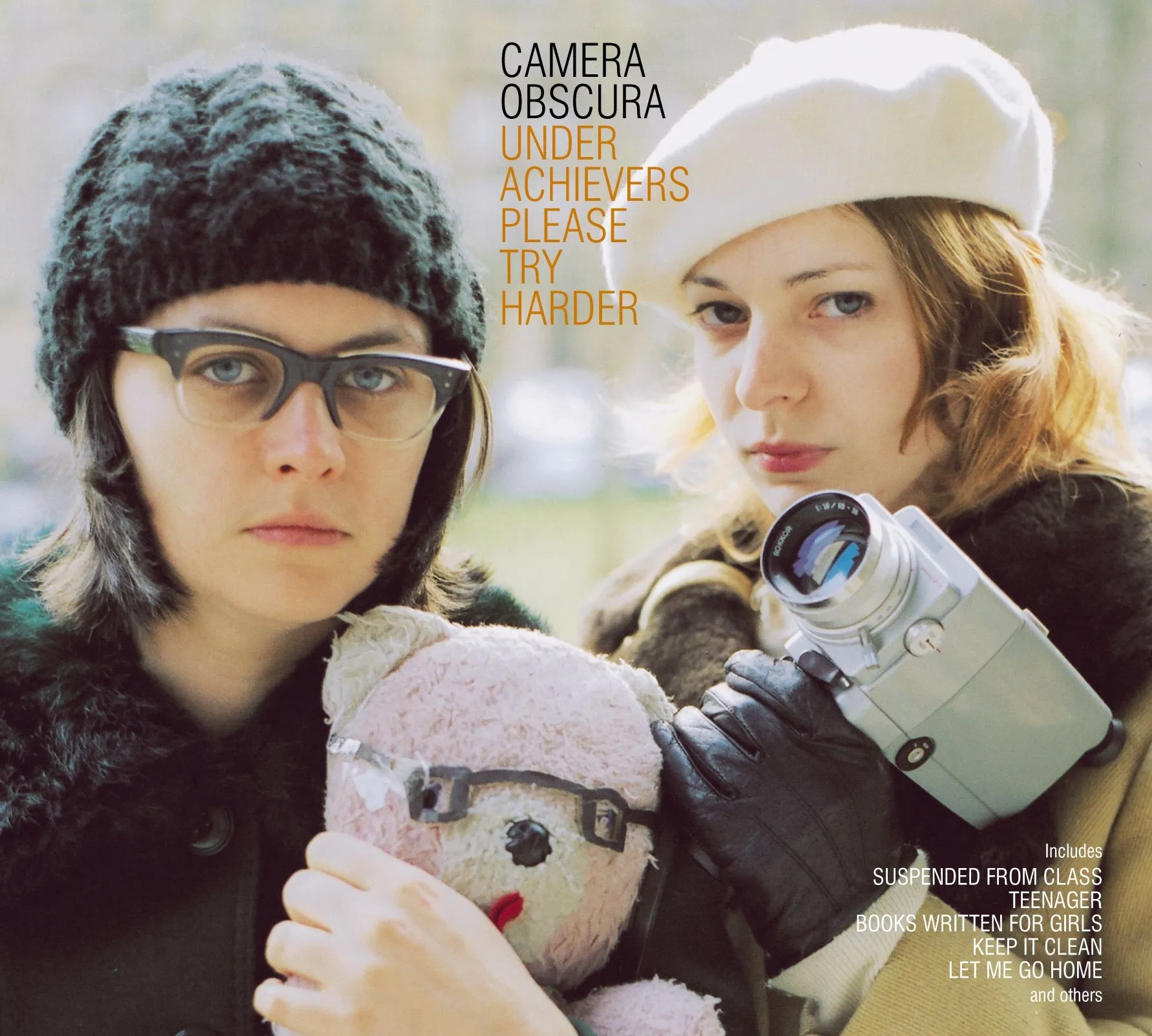

Camera Obscura - Underachievers, Please Try Harder (Vinyl LP - orange)

Camera Obscura - Underachievers, Please Try Harder (Cd)

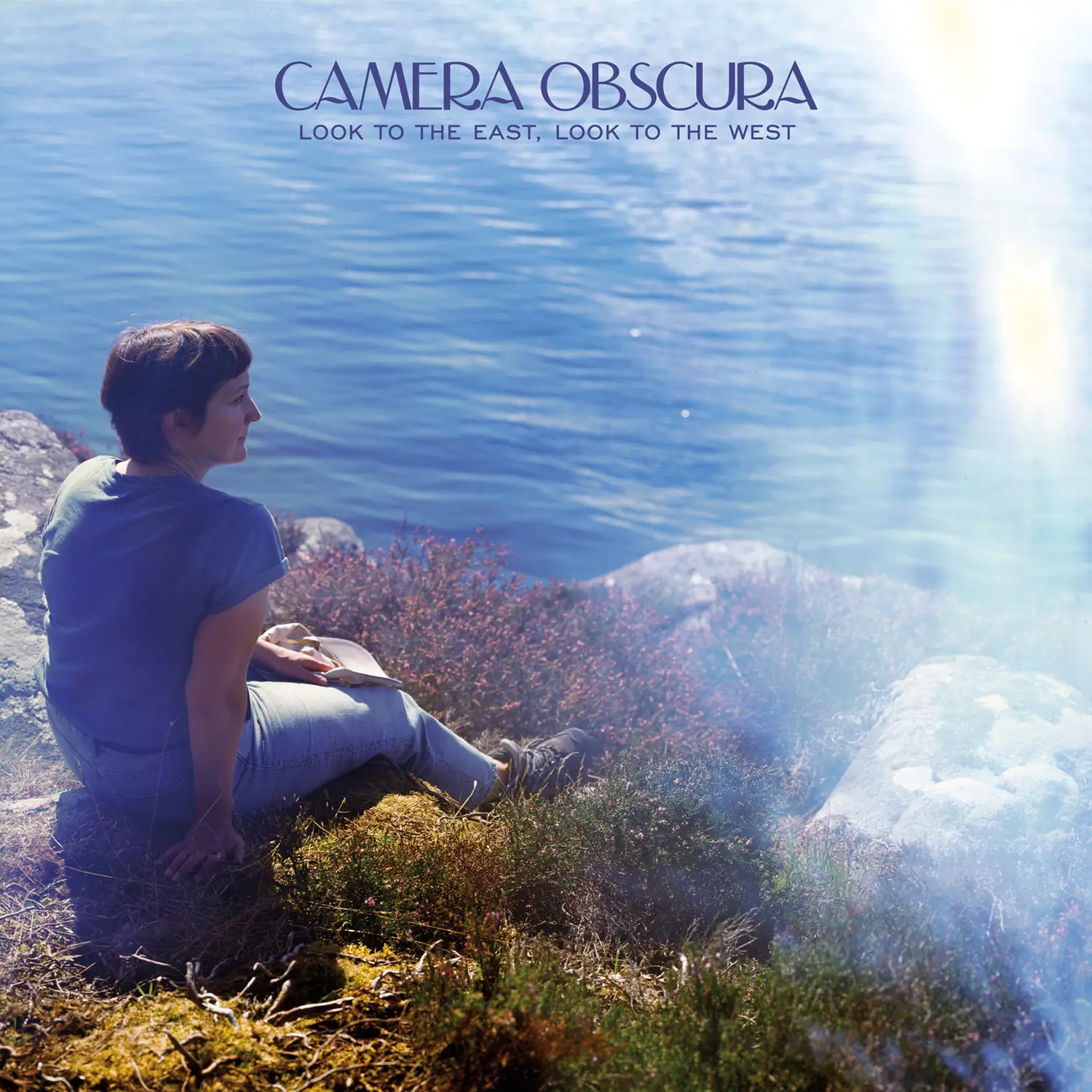

Camera Obscura - Look to the East, Look to the West (Vinyl LP - black)

Camera Obscura - Look to the East, Look to the West (Cd)

Camera Obscura - Look to the East, Look to the West (Vinyl LP - violet)

Camera Obscura - Let's Get Out Of This Country (Vinyl LP - clear)

Read More

Belle & Sebastian announce Boaty Weekender Cruise Lineup with Mogwai, Camera Obscura, Django Django, Alvvays and more

The music festival at sea will sail from Barcelona to Cagliari, Sardinia next summer!

6th September 2018, 12:00am

Camera Obscura, O2 ABC, Glasgow

The indie pop stalwarts play an eagerly-anticipated home town date.

6th March 2014, 12:00am

Camera Obscura - Desire Lines

4 Stars

Camera Obscura have come up trumps.

1st June 2013, 12:05pm

Listen: Camera Obscura Showcase New Track ‘Do It Again’

'Do It Again' was premiered on Marc Riley's BBC 6music show yesterday.

16th April 2013, 3:06pm

With Rachel Chinouriri, A.G. Cook, Yannis Philippakis, Wasia Project and more!