Cover Feature Core Strength: Fall Out Boy

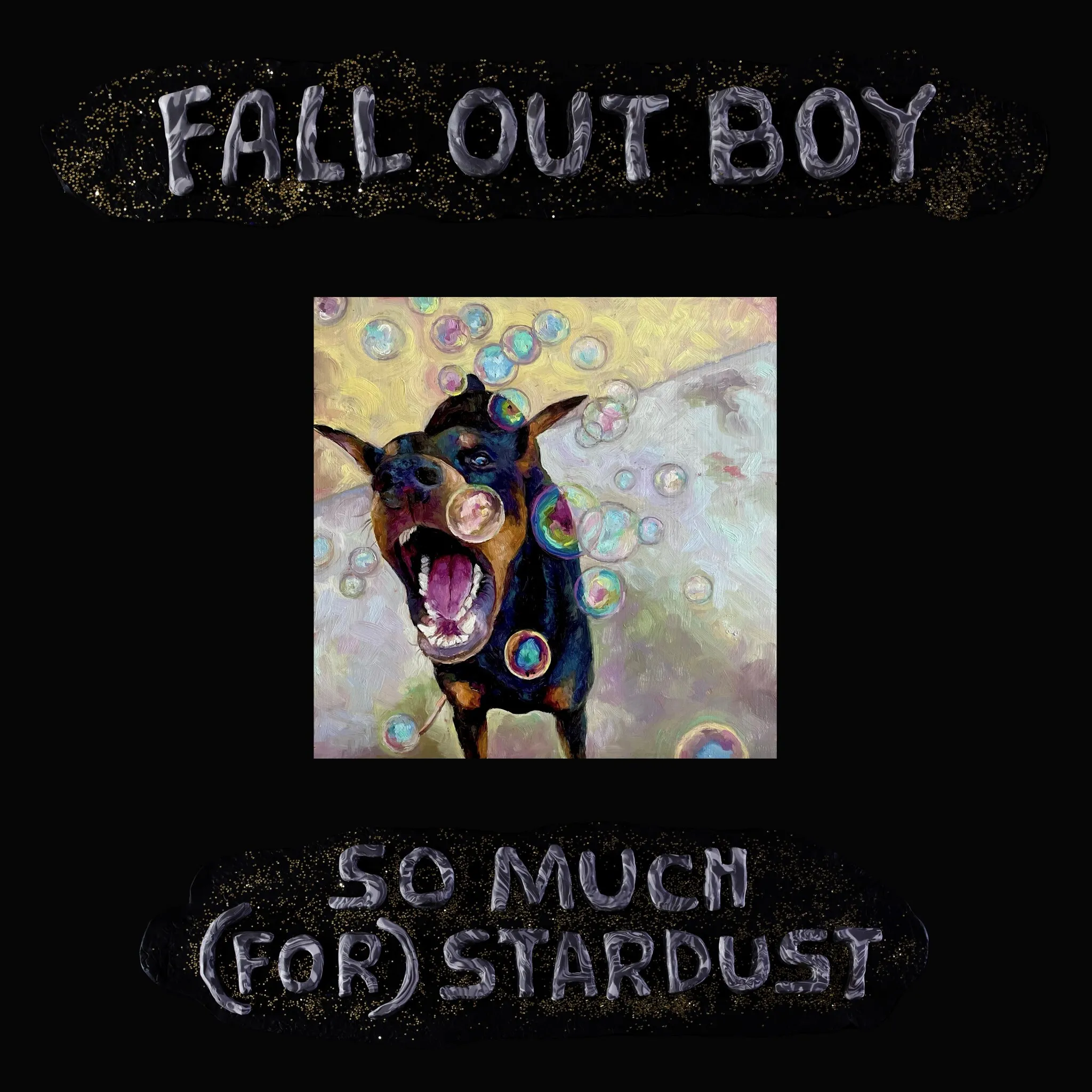

After five years away, Fall Out Boy are going back to their roots with ‘So Much (For) Stardust’: an album that embraces their origins with the older, wiser heads of seasoned pros.

Speak to Patrick Stump and Pete Wentz about Fall Out Boy’s new album ‘So Much (For) Stardust’ and you’ll get conflicting reports as to whether the record was, for a period, even going to exist. It comes over five years after ‘M A N I A’, their experimental seventh record, making this the longest break in the group’s history. Frontman Patrick, who started writing not long after ‘M A N I A’, insists that break wasn’t intentional; “I wanted to take a little break, but for us, that’s usually months. It wasn’t a big deal,” he begins. For bassist and chief lyricist Pete, however, the pandemic had complicated things. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to keep doing this,” he counters. “I became a pandemic baby, I was so nervous about leaving the house. When you’re with your family, you become a wolfpack. If I was going to leave my family and my house, it had to be for an important reason.”

“I can vouch for that anecdote. Pete sent me so many texts like, ‘I don’t know that I want to do a record’,” says Patrick. But soon he gave Wentz an all-important reason: he’d started to write an album that could drag his bandmate out of that deep hole. “I didn’t believe him, because when he and I get excited about something, it’s gonna happen,” Patrick continues of that jeopardy period. “I started to get excited and I knew he was going to get excited. If you build it they will come.”

Though it took Wentz longer to come around, he says that the record benefited from this break. For ‘So Much (For) Stardust’, Fall Out Boy wanted to bring it back to basics - or as close to basics as a band so fond of an orchestra can get. They returned to pop-punk mecca label Fueled By Ramen, and got back in touch with Neal Avron - the producer they’d last worked with on 2008’s ‘Folie à Deux’.

“It took a long time to get Neal locked down because he doesn’t [produce] much now. He’s a multi-GRAMMY-winning mixer,” says Patrick. But, with 15 more years of musical evolution and education behind them, Stump was keen to show Avron what the band could be capable of. “I didn’t know anything about horn arranging when I was 23. Now I know quite a bit about it, and I was able to bring that to the record and to Neal,” he continues. “I didn’t want to push any specific musical agenda in terms of how [the album] should sound; I wanted to see how the cards fell. I knew that we were such a different bunch of people at this point.”

With regard to the shift that happened once the producer was on board, Stump references film director Sidney Lumet, who once said that you need everyone on a production to feel like they’re making “the same movie”. With Neal Avron, every member of Fall Out Boy was making the same album. “‘M A N I A’ was a really big experiment and I loved making it, but it didn’t have a central producer,” says Patrick. With one in place, they found a missing cohesion. “We could throw anything at him and he was still in the centre, pulling those ideas down to where it all makes sense.” Wentz adds that going back to Avron felt like a homecoming. “It’s like going back to your childhood bedroom, but you know you can go downstairs and drink a beer in front of your parents,” he laughs.

The record came together faster than anyone was anticipating. Flying to LA, in theory just to lay down some initial demos and test the waters, the band immediately found things clicking into place. “That week and a half was so remarkably productive. Some of the songs that ended up on the record were almost completed in that one session,” says Stump. “It was supposed to be us just testing it out, but we came away with almost half of the record completed in one week. That was a big turning point.” The rest, meanwhile, was recorded in the second half of last year, coming off the back of Hella Mega: their monster tour with Green Day and Weezer. “If you’re playing baseball stadiums sandwiched between these two iconic bands, you better put out a good album,” says Wentz. “That experience sharpens the art.”

‘So Much (For) Stardust’ is a true homecoming for Fall Out Boy. On it, they eschew the pop simplicity of 2013’s ‘Save Rock and Roll’ and the chaotic experimentalism of ‘MANIA’ in favour of something that hits older touchstones without falling victim to nostalgia. It’s a big record, full of orchestras, rock guitars, horn arrangements and the wide range of musical references you’d expect from a group of guys with such diverse tastes. The tracks feel touched by influences ranging from ‘70s pop to Danny Elfman to Fiona Apple to ‘80s movie soundtracks, with just enough film references thrown in to make the whole record feel like only one thing: a Fall Out Boy album. The most notable shift, and one older fans will be grateful for, is the return of those verbose lyrics that made the band simultaneously the subject of so much mockery and adoration.

Memes about Stump’s voice, or his difficulty cramming Wentz’s lyrics into a singable form, abound. Mishearings of Fall Out Boy songs - particularly on second LP ‘From Under the Cork Tree’- litter the internet. It got to a point where it really affected the vocalist. “Fall Out Boy being difficult to understand became such a meme and it hurt my feelings, I really internalised it,” he says. “I thought, ‘Oh, I’m a bad singer and no one can understand what I’m saying’.”

Stump, who first auditioned to be in Fall Out Boy as a drummer, says that the unintelligibility is in part because he wasn’t originally a singer by trade. Despite having one of the clearest, most impressive voices in alternative music from 2003’s ‘Take This to Your Grave’ onwards, he says that he didn’t know how to sing. “I was a drummer and occasional multi-instrumentalist,” he explains. “Pete and Andy [Hurley, drums] were in real bands that really toured, which was legendary to me, so I wasn’t taking the band very seriously. I was like, ‘They’re going to go off on tour. This is really fun for me, but for them it’s a side gig’. I didn’t know what I was doing and I was trying to not get too emotionally invested. I thought there’s no way this is going to last.”

However, after signing with Island for 2005 breakthrough ‘From Under the Cork Tree’, it became clear that Fall Out Boy was more than a side gig for four hardcore boys from Chicago. With Wentz writing all of the lyrics for that album, he and Stump started getting into arguments about what it was humanly possible to sing. “There are a lot of parts where you can hear the push and pull. There are some lyrics where Pete was like, ‘No, it has to be this word’. I’m like, ‘There is no physical way to sing that word in this many syllables in this many beats’. You’re also trying to bend it so it rhymes, even though it doesn’t. Those vowels get very mushy,” he says. It’s, of course, most audible (and memeable) on ‘Sugar We’re Goin’ Down’, but there’s a charm to their style that touched a generation of teenagers - a charm Stump hears now. “It’s interesting hearing the thing form and come together,” he says.

It’s the memes, in part, that necessitated the lyrical simplicity of Fall Out Boy’s post-hiatus records, from ‘Save Rock and Roll’ until now. “I started pushing for more streamlined choruses that were easier to sing and easier to discern,” Patrick explains. “[With this new album], our manager sat me down and said not to do that.” Indeed, it’s clear from ‘So Much (For) Stardust’’s first single, ‘Love From The Other Side’, that the band are shunning the simple choruses of recent years in favour of the verbal dexterousness of old. Wentz references The Avengers: “It was like when Captain America is like, ‘Hulk, smash!’ Let Patrick out of the cage! Patrick, you’re free! Be Fall Out Boy!”

While the pair do still go back and forth on what it’s possible to sing, they’ve found a middle ground. “Pete is very precious, it’s like The Princess and the Pea,” Patrick says. “He’ll send me these lyric sheets and I’ll change three words to make it fit. He’ll hear it and be like, ‘I got to change those words, I messed it up’. You don’t remember that you didn’t do it, but you know it’s not right.”

20 years deep into working together, both Stump and Wentz are candid about how much they used to argue. But it seems almost funny to them now, like they’re looking back on two fiery kids. “There’s something to be said about how, on the earlier records, we fought. I can hear this fighting, and the push and pull in the songs - and that does make for great art, but 20 years later it doesn’t make great art. You’re just two assholes,” says Wentz.

With age has come understanding and a way of working together. Fall Out Boy is still the core four-piece unit it’s always been, and it’s clear that they’ve found a secret to longevity that many bands have not. “Having that trust there allows you to make art in a different way. Going ‘Fuck you, fuck you’ - it’s not sustainable. It ends up being bitter,” says Pete. “So I appreciate that there’s this trust there now.” Patrick adds: “It amazes me when I talk to other bands. Everyone’s got complaints, but the tenor of it is very different when you hear us complain about each other now, because we’re still good friends and we enjoy each other’s company. Sometimes you’ll be out to dinner with another band and you’ll be like, ‘My guy does this’, and they’re like, ‘Don’t you hate him?’ Like no, actually. It’s possible to not have egos and get on pretty well.”

They attribute at least part of that to getting older and becoming parents. With less time to get anything done, they need to be “laser-focused” when rehearsing or recording. “Time away is so important and so much smaller. In some ways I feel like it streamlined the art,” says Wentz. But in part, at least, their continued kinship is due to a lack of ego that takes down so many other bands. Stump puts this down to their pasts in the hardcore scene. “There would be moments where if somebody had the part, they just played it. It didn’t matter what the so-called line-up was. We have the line-up on the record, but there are times where we’ve switched that up because, like, ‘You play it faster, you just do it’. I think that sets a tone for the whole ego thing. That was something, Pete, you really taught me,” Stump says to his bandmate. “If you can play it faster or if you have the groove, just play it. We’re all working towards the vision.” Even on ‘…Stardust’, they’ve switched up who plays which guitar parts. “If we’re gonna fight about this chord or this lyric, we’re never gonna get anything done,” the vocalist shrugs.

Wentz cuts in to make a characteristically niche sports reference. “In the late ‘80s, the hockey team the Redwings imported these Russian players, and they were unbeatable for two years because they play a different style of hockey which is called ‘In service of the puck’. Your job is to help get the puck down to the goal. We try to always operate like that with Fall Out Boy, but this record is the truest spiritual sense of that,” he says. “If you just want attention, you’re going to have it sometimes and you’re going to not have it sometimes. It’s inevitable that at some point you’re going to lose,” adds Stump. “I’m not a competitive person, I never have been. I can’t care enough about winning or the idea of defeating somebody else. But I’ve always been competitive with myself. I want to be a better writer or singer than I was yesterday, and that’s something you can do forever. But you’re not going to be the cool, young, sexy thing forever. There’s definitely a time limit on that.”

Despite ‘So Much (For) Stardust’ in many ways bringing Fall Out Boy home and back to basics, the band’s eighth is still full of anthemic songs that seem primed for an audience to sing back at them. However, they have a different texture than the stadium tracks on ‘Save Rock and Roll’ or 2015’s ‘American Beauty/American Psycho’ - in a large part down to the more personal nature of the record’s lyrics, which explore neuroses, heartbreak and pandemic anxiety.

“Lyrically, it makes more sense to go deeper now. You go deeper with people, and those people care more, and it makes it that much more anthemic because they believe what they’re singing,” says Pete. An anthemic song doesn’t need to be a general one; if you have a room of 10,000 people singing something that they each personally relate to, it’s going to feel that much bigger. “If it were something you could contrive, you would make the song that was the most palatable to the most people,” he agrees. “But when you get in that cycle, you start to shave off the edges and the identity of it.”

With the album still not out in the world when we talk, neither musician knows what the response to it is going to be. They liken the wait for reaction to lots of things – wine that’s gone bad in the bottle; a dead cat in a gift box – that a person might not like to open. But, if the response to ‘Love From The Other Side’ is anything to go by, they don’t have much to worry about. “I was totally taken aback,” says Patrick. “I was like, ‘This song is too weird, the lyrics are too big, I have an orchestra’. I thought this is going to be a fun song for us, but I don’t know that the audience is going to go for it. But the response has been overwhelming, and I think it goes to show that honesty does better.” Wentz agrees: “In a world of inauthenticity, authenticity cuts through.”

The build-up to the announcement of ‘So Much (For) Stardust’ and the release of ‘Love From The Other Side’ included the band sending out postcards from ‘pink seashell beach’. It’s a reference to Gen-X movie Reality Bites, a pretty nihilistic reference for such a cute image. The album itself features Ethan Hawke’s speech from the movie where he realises that life is essentially meaningless - something Wentz has struggled with. “Every Fall, I get a weird matriculation, like my parents are older, I’m older, my 14-year-old will be moving out soon. Thinking about time speeding, I thought about that specific clip a lot because there’s a danger of going, ‘What’s the fucking point of any of it?’ That’s a scary thought. It’s easy to think, ‘We’re in a slow march to the end’,” he says. But this record is a way of working through that nihilism and shaking things up. “You have to do something to break out of that. You have to do something that’s a little bit crazy. You have to sing in the band instead of playing drums. We had to work with Neal again.”

And so, the biggest secret to holding it together after so long, it seems, is as simple as just getting along; as just being a band. “I needed to write with Patrick again,” Wentz considers of fighting the fear and getting back in the ring. “I felt a little shell-shocked and wanted to be in my house, but when we’ve gone to play shows since then, we go out and we eat together and hang out. You have to do these things instead of sitting in a hotel room and pondering your inevitable death.” Stump interjects, laughing: “Doesn’t that sound like fun? That’s not your weekend plan?” That push and pull, finding a middle ground between nihilism and optimism, is both the spirit of ‘So Much (For) Stardust’ and of Fall Out Boy as a whole. Long may it continue.

‘So Much (For) Stardust’ is out 24th March via Fueled By Ramen.

As featured in the March 2023 issue of DIY, out now.

Read More

Download adds Frank Carter & The Rattlesnakes, Enter Shikari, Tom Morello and more to 2024 lineup

They join already announced acts like Queens of the Stone Age, Fall Out Boy, and Royal Blood.

30th January 2024, 1:42pm

Fall Out Boy - So Much (For) Stardust

4-5 Stars

A real joy.

24th March 2023, 12:00am

Fall Out Boy announce 2023 UK/EU tour

PVRIS and Nothing, Nowhere will be coming along for the ride too.

8th February 2023, 12:00am

Fall Out Boy release new track ‘Heartbreak Feels So Good’

It’s the latest preview of their new album ‘So Much (For) Stardust’.

25th January 2023, 12:00am