Interview Nils Frahm on making music that lasts

Building his own studio in Berlin’s Funkhaus for new album ‘All Melody’, the composer is continuing to forge his own path.

Concepts have always attached themselves to Nils Frahm’s albums like glue, whether intentional or not. From recording the entirety of 2012’s ‘Screws’ with nine fingers due to a broken thumb, to the previous year’s ‘Felt’, where he placed said material over the keys of his piano to allow him to play late into the night, there’s a poetic originality that has latched onto each of his studio releases.

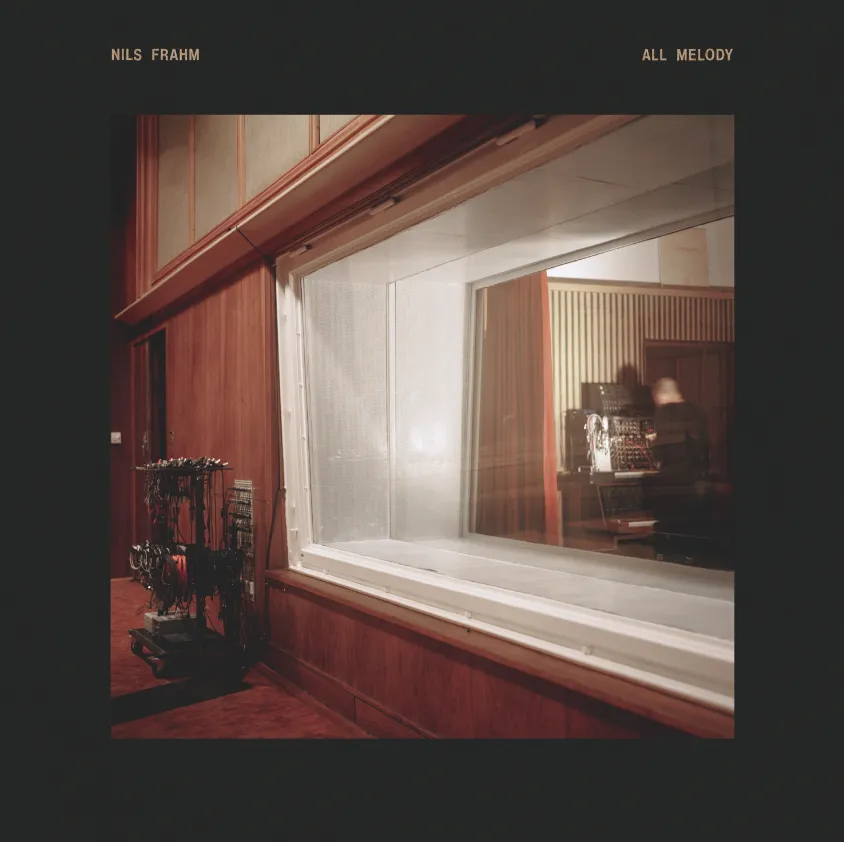

For new album ‘All Melody’, seventy-five minutes of gorgeously arranged compositions that melt together the acoustic and the synthetic seamlessly, he built a studio from scratch in a wing of Berlin’s iconic Funkhaus. Held up as one of the most celebrated figures in the neo-classical world, Frahm found the time and space to isolate himself for nearly two years, immersing himself in what may be his best album yet.

Sitting in the East London office/gallery of long-time label Erased Tapes the morning after sharing the album with a handful of press at a listening party - only hours after it was officially finished - the relief Frahm feels is palpable.

“I didn’t think it wouldn’t happen,” he begins, musing on the idea that ‘All Melody’ might never have been finished in the way that he intended. “I was just afraid of what it would be. I’m very aware that, in the end, you have an optimum: you have a framework, and then do whatever you can to get the best out of [that framework], and it’s a little bit like having a bunch of ingredients, and saying ‘What’s the best meal I can make out of this?’”

“It seems to be inspiring to people, to watch me living in the field of the uncertain."

“In this case, I'm really happy,” he continues, “because I was able to select from a lot of good material, and to be in the position to dedicate so much time to it. It doesn't really matter how comfortable I feel with it after it's done - it matters how much other people like it. I'm not making the album so I can listen to it every day. I'm not listening to my albums much at all once they're out. I don't need that music in my life. I had it while I was making it, and now it's yours. If you don't like it, it doesn't matter how much I love it.”

Adhering to the wishes of fans isn’t something that the composer takes into account when making music, but it’s one that’s become inextricably tied to his process: largely, how he’s cultivated a fanbase that allows him the time and space to rush nothing, and has confidence that whatever comes next will be worth the silence.

“I don't think anybody wants anything else from you, except that you try,” he begins. “The implication I had for this album was that I am now essentially sponsored by my fans to do whatever I want to do.” As he points out, it reflects in the ticket sales. Without a second of music released from ‘All Melody’, four nights at London’s Barbican sold out almost instantly. “People want to be part of it, and to see what comes next. And they trust me.”

“It seems to be inspiring to people, to watch me living in the field of the uncertain,” he continues, “because not many people can allow themselves to exist in that way. It can inspire people who are more hesitant. With big life decisions, they find themselves not being able to just cut free, and then they see me just hammering away at a piano with some toilet brushes, and can achieve that feeling for a little while, and work past shame, and fear, and other things that are bothering them. That's my soundtrack. It's something liberating.”

It turns out the same kind of revelations come to Frahm himself when finishing a song. “[Writing music] is making me emotionally smarter,” he says. “It changes me. In my childhood too, the people I was listening to - people like Miles Davis - they changed my life forever. That music is so strong, and I try to imagine a society without that music. What would that look like? Nobody knows. It would be interesting to make a dystopia of humans without music. It would be so impossible to imagine. I want to make music that sounds like it’s always been there, but that you’ve just never heard before.”

“I want to make music that sounds like it’s always been there, but that you’ve just never heard before.”

Throughout its extensive running length, ‘All Melody’ bristles with life. From the choral vocals of ‘Human Range’, which rise and fall in dramatic waves, to the intense woodwinds of ‘Sunson’, it’s Frahm’s most intricate, human work to date. “I realised this yesterday,” he begins, reflecting on the perfect silence of his new studio, before a London bus roars past the window, right on cue. “In London, or New York, there's always a sound, wherever you are. There's so much less room for the music. That's a part of Germany: the desire for quietness. Bathrooms have no fans; houses don't have loud ACs. A lot of why people like Berlin so much is that they love the acoustics of it. I realise it so much. Coming back to Berlin from New York or London, it feels so soundproof.”

Though it flows seamlessly, ‘All Melody’ is still a chunky listen, and Nils notes the current irregularity of listeners sitting down and digesting a 75-minute album with no distractions. It places him slightly out of step with the current climate, but his refusal to be swayed by listening trends is a concrete one.

“We're in a time where singles are important,” he states, tracking the landscape from “7s in gas station jukeboxes through the age of the long player and now to streaming services and playlists. “What will it be in 10 or 20 years?” he asks, one of a host of rhetorical questions he poses and then answers almost immediately. “My feeling is that we will appreciate the album again. It's a great format. We need to give a little bit of time to have a musical experience of a certain depth. You cannot make a musical journey in one minute thirty. Making good albums is really hard.”

In step with his music sounding largely timeless, an appreciation of the future is at the heart of ‘All Melody’, even if it brought about some disagreements when arriving at the finer details of finishing the album. “I don't want to have this squashed, loud album which doesn't sound right to my ears, just because of Spotify's technicalities,” the composer replied to being asked to alter the master of the album to better coincide with the streaming service’s algorithm, which modifies the volume of the songs.

“Who will think about that in 50 years,” he reflects now, “when someone picks up the record in a flea market, and says 'Wow, this is really old! Let's listen to it!' and brings it home and thinks 'Oh, this sounds horrible!' because it was created in the days when everyone mastered for laptops, iPads and Spotify. And I can say 'Well a few people didn't! Listen to this - it sounds amazing!' The only way I'm having success in my own way is because I'm doing the opposite from what is asked [of musicians] at the moment. If I look back at any success I have, I can say that it happened because I was never compromising.”

“What will it be in 10 or 20 years? My feeling is that we will appreciate the album again.”

“Absolutely,” Frahm replies firmly, the first time his voice is even slightly raised, asked if he’s happy with listeners digesting his music but learning nothing about the man behind it. “I hope that is the main focus. If people feel like they need to see more of the person to like the music, then a lot of music would probably be ruined. Like, hey, Beethoven was probably a crazy neighbour.”

“In the 20th century, we reached a point where it all became a bit too much,” he expands. “We lost god, and lost a belief in something higher, and what remained were superstars. Superstars are never god-like; they're still human, and deep down we know they are not really better than us. With Michael Jackson, with Fleetwood Mac, with Queen and all of these huge stars, I feel like we were participating in some sort of irony: how could we turn certain humans into gods? They're not perfect at all.”

Though his refusal to conform to widespread changes in ideas and listening habits might look like it threatens to push the composer into irrelevance, it’s the determination with which he sticks to his guns on ‘All Melody’ that makes his draw so strong, and his perch at the very top of the neo-classical world so stable.

“I feel like it's the most interesting time in music and culture right now,” he reasserts, far from shunning any forward movement in favour of romanticising the past, “because we have the internet, and a new self-understanding of a society which is no longer willing to turn silly humans into gods. We can focus more on the content now, and less on the glitter.”

Nils Frahm’s new album ‘All Melody’ is out 26th January via Erased Tapes.

Photo: Alexander Schneider

Read More

Gorillaz, Brockhampton, Nils Frahm and more kick off an eclectic first day at Lowlands 2018

Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever, Amyl and the Sniffers and Protomatyr also played standout shows on day one of the Dutch festival.

18th August 2018, 12:00am

Nils Frahm - All Melody

4 Stars

Once his melodies spin, there’s really no stopping them.

26th January 2018, 7:52am

Watch Nils Frahm cover John Cage’s ‘4’33’ ahead of ‘Late Night Tales’ mix

Curated release comes out this week.

9th September 2015, 12:00am

Watch Nils Frahm perform ‘Says’ at the BBC Proms

The Berliner played London's Royal Albert Hall last night.

6th August 2015, 12:00am

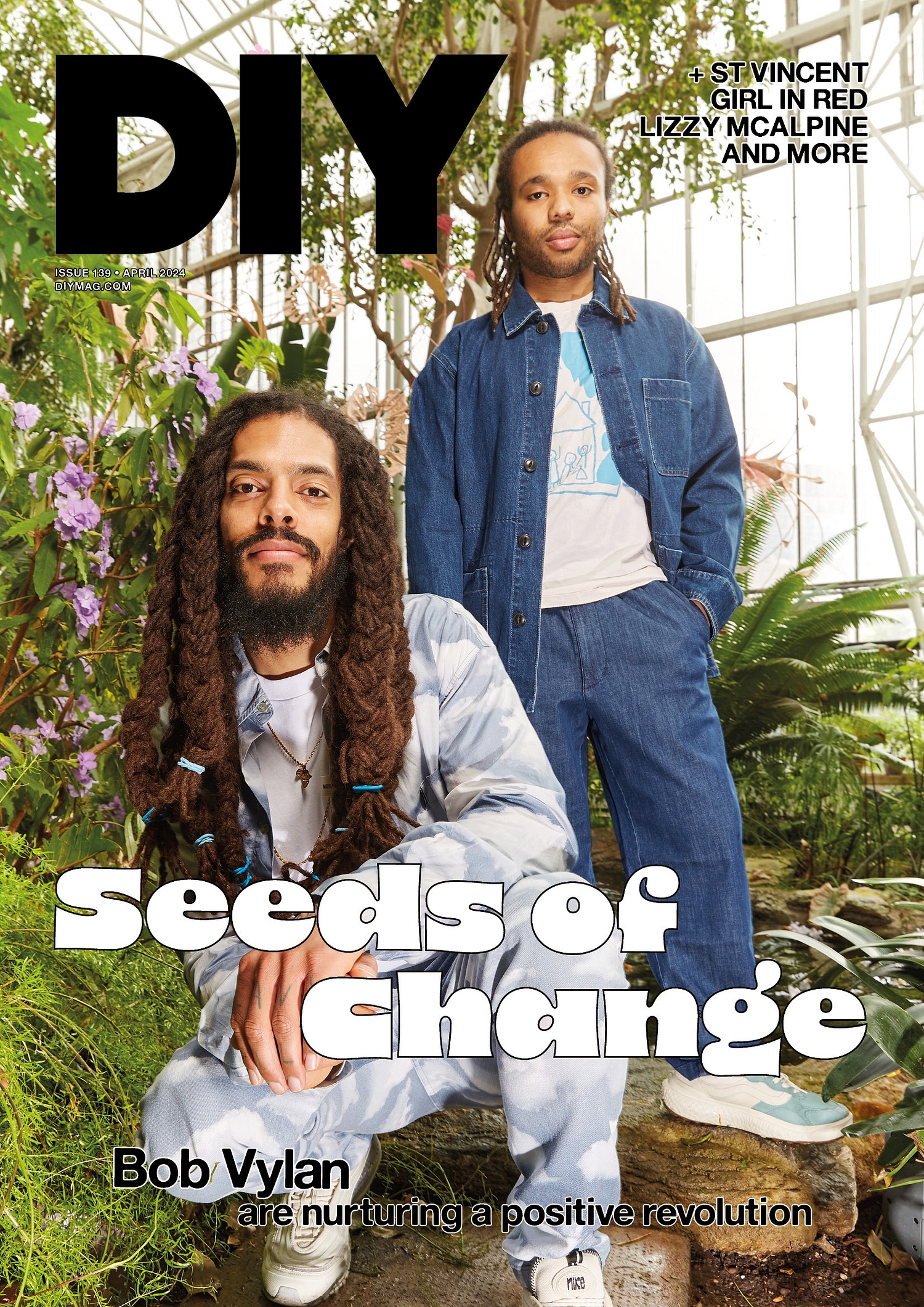

With Bob Vylan, St Vincent, girl in red, Lizzy McAlpine and more.