Interview Tune-Yards: “There Was A Lot Of Self-Doubt”

Tune-Yards is forging her own path, mixing hip-hop, a studio in the desert and darkness.

“Let’s not pretend that the world around us isn’t falling,” Tune-Yards’ Merrill Garbus sweetly sings on ‘Nikki Nack’’s fifth track, ‘Look Around’. She’s right. We’re often attempting to disconnect from the reality of the state of the world - staring down at our shoes whilst walking and not taking a second to look up to notice the buildings above are getting higher and increasing in density. It’s a subject that Merrill has thought about a lot and comes back to often, but perhaps not something she expected to discuss whilst eating breakfast, in her hometown of Oakland, California.

The more left-field sounds that feature on the new album include a bag of rice, water bottles, a vinyl stool and lampshades and for her, these background sounds are really important; organic sounds as objects - as tangible things you can touch and see. “I think that’s a great way to put it,” muses Merrill. “I definitely come from more organic sounds and I miss them when they’re not there. We live in a very synthesised world in a lot of ways, a very digital world. It’s always nice to remind ourselves of the organic and the natural. If we’re not reminded of that then the implications are really scary.”

One of the ways in which she did this for herself was going to Haiti, a trip that she’s keen to explain was only part of her journey making this album. “I’ve been not wanting to call this the ‘Haitian Tune-Yards album’ because it just isn’t that,” she carefully states. “The trip to Haiti was part of my musical education that we went through with this album. Nate [Brenner, bass] and I both took lessons in Haitian drums, I took Haitian dance lessons. Where I ended off at the end of the ‘W h o k i l l’ tour was just feeling like I had done all that I had in me and so it was important to rejuvenate my creativity and my sense of what I have in store musically.”

Touring didn’t just affect the creativity though - with the incredible range of Merrill’s voice, it’s something that she has to take precautions with. “I have to get a massage on my throat because my throat gets so tense. That was another reason to take voice lessons, to make sure that I’m using my voice correctly. I wish a tour was just fun drinking parties but that has become less and less the reality which is good because it means I’ll probably live longer,” she continues, “I’m not wasted on stage, that’s for sure. With the looping, I can’t do any drugs or alcohol before the show - they’re just out of the question.”

In terms of Tune-Yards’ live show, dancing is a big part of it and that’s something that translates to their recorded output. “I try to dance as much as possible. It’s a new level of connecting with what my body’s doing and that’s been wonderful.” It’s an art form which she would like more people to take seriously and participate in. “I don’t think we value dance enough in our culture. In Haiti, dance and music is inextricably linked with the revolution. Everything to do with their folkloric culture is part of the story of how they won their independence. You’re dancing in a particular spiritual energy and that was really powerful to me – a dance being a very powerful art form. I don’t go to a lot of raves but I think what people get from them these days is a transcendence. You’re transcending reality and getting in touch with something deeper you can’t put words or sounds to.”

Being able to put sounds to “something deeper” is what the process of ‘Nikki Nack’ and being in Tune-Yards is about, and to do that Merrill drew from a variety of influences. “American folk music is one, there’s a little bit of traditional old, tiny fiddle on ‘Rocking Chair’ and a little snippet of my Dad playing one. I think folk music in general from Appalachia, where my parents brought me up with that music around in our household. ‘Time of Dark’ was very influenced by Khaira Arby, she’s this wonderful singer from Mali and we listened to a lot of her. It all gets filtered through what Tune-Yards is – a really fun and deep project for me and Nate.”

This deepness is reflected in some of the darker themes explored on the record, including ‘Stop That Man’ which alludes to George Zimmerman – the murderer of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin who was widely regarded as unfairly acquitted. It was also a dark period in Merrill’s life. “There was a lot of self-doubt, a lot of looking at myself honestly and without the lens of success and people applauding for you every night. I was really burned out at the end of the last touring cycle and scared. I think that’s where most of my dark feelings come from, feeling scared. The things that we often do to get rid of fear are often so self-destructive – turning away from reality and from life and wanting to step away from our real lives. Watching myself do that and watching what I saw made me want to really get honest with myself about my behaviours and how I could grow as a person – growing as a person as well as a musician is really important to me.”

She stops for a second, laughing to herself. “I could go on but you’re not my therapist.” Success is not always everything it’s made out to be and she makes a clear point of trying to stay away from getting comfortable with it. “Having that kind of success, it’s not like I’m Lady Gaga but for me, having that new notoriety – it can really fuck with your head and I wanted to stay grounded and humble, in reality. Not in a fantasy that I’m going to be able to afford every health food that I could ever want and houses in the Hollywood hills. This is still a job, it’s still very hard work and it may not be what I want long term. I have to think, ‘What do I want out of music? What do I want out of my career? And what do I want out of this band?’ At the end of the day, this is just work.”

Hip-hop is a particular love of hers and she name checks The Roots, Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean as artists she admires. She also acknowledges that it’s very much part of the lifestyle that she herself doesn’t want to become too enwrapped in. “All successful music gets commercialised. Tune-Yards is getting commercialised and at some point, I might wish for an album to not get critically praised. I want to keep making music that has depth too and I think it’s hard to write over decades. There’s always a danger of getting watered down and that’s why I wanted to travel to Haiti and study a music I’d never studied before, because I wanted to deepen my own sense of what’s possible and not do what every other band is doing right now.”

For ‘Nikki Nack’, they brought in big pop producers in the form of Malay (Frank Ocean, Angel Haze, Big Boi) and John Hill (Shakira, Rihanna, M.I.A) – which was a decision Merrill was very unsure about because she loves to be in complete creative control, but it was an experience that turned out better than she could have hoped for. “Malay worked on ‘Hey Life’ and ‘Wait For A Minute’ and it was a beautiful lesson in production. What he showed is that we didn’t need much more than we already had. He worked his magic with creating some very nuanced sounds that you can barely hear. They’re atmospheric with these really simple touches. He created this full sound. It was only on a handful of these tracks and they were so respectful of what Tune-Yards already was, respectful of each song. They’d be like, ‘Okay, this song is great already – how about we exercise this kick drum?’ It was more that they brought out the good in any song and cleaned it up, simplified things.”

The album was recorded in various places, including a studio in Oakland and in the desert – it reflects the wide variety of influences on ‘Nikki Nack’ and although it was a challenge, it was the most straightforward recording of a Tune-Yards album. “The whole process was rather chaotic, it felt like ‘What are we doing?’ I think now I understand that’s the nature of a Tune-Yards album, it’s very patchwork-y. I don’t know if you’d call it normal but we wrote songs, we wrote some demos, we went into a studio for two weeks so we just do the whole thing and then we mixed it. It’s never been so straight forward and I think the reason for that is that it took place in the editing. There was a whole lot of amazing variety; it was up to me a lot to make sure that the album as a whole feels like it’s a cohesive album. That’s where I’m the producer, I really need to make sure that the vision is clear and that it feels focused.”

A song in particular that feels very different and sounds like a nightmarish children’s bedtime story is ‘Why Do We Dine On The Tots?’ It was rooted in a puppet show that Merrill created in her 20s. “It was based on the Jonathan Swift essay Modest Proposal, a satire about eating babies as a solution for poverty and hunger. I discovered it in a journal, rifling through for ideas I might’ve possibly had years ago. It seemed to really ring true, maybe I’m getting more comfortable with making an album like ones I grew up with – one that not only has music but that has some kind of world to it.” The themes on ‘Nikki Nack’ stem from this idea and Merrill finishes with a confirmation of that, “To me, a lot of the album is thematically about eating the future of our future generations.”

Tune-Yards’ new album ‘Nikki Nack’ will be released on 5th May via 4AD.

Taken from the May 2014 issue of DIY, available now. For more details click here.

“I try to dance as much as possible. It’s a new level of connecting with what my body’s doing and that’s been wonderful.”

Touring didn’t just affect the creativity though - with the incredible range of Merrill’s voice, it’s something that she has to take precautions with. “I have to get a massage on my throat because my throat gets so tense. That was another reason to take voice lessons, to make sure that I’m using my voice correctly. I wish a tour was just fun drinking parties but that has become less and less the reality which is good because it means I’ll probably live longer,” she continues, “I’m not wasted on stage, that’s for sure. With the looping, I can’t do any drugs or alcohol before the show - they’re just out of the question.”

In terms of Tune-Yards’ live show, dancing is a big part of it and that’s something that translates to their recorded output. “I try to dance as much as possible. It’s a new level of connecting with what my body’s doing and that’s been wonderful.” It’s an art form which she would like more people to take seriously and participate in. “I don’t think we value dance enough in our culture. In Haiti, dance and music is inextricably linked with the revolution. Everything to do with their folkloric culture is part of the story of how they won their independence. You’re dancing in a particular spiritual energy and that was really powerful to me – a dance being a very powerful art form. I don’t go to a lot of raves but I think what people get from them these days is a transcendence. You’re transcending reality and getting in touch with something deeper you can’t put words or sounds to.”

Being able to put sounds to “something deeper” is what the process of ‘Nikki Nack’ and being in Tune-Yards is about, and to do that Merrill drew from a variety of influences. “American folk music is one, there’s a little bit of traditional old, tiny fiddle on ‘Rocking Chair’ and a little snippet of my Dad playing one. I think folk music in general from Appalachia, where my parents brought me up with that music around in our household. ‘Time of Dark’ was very influenced by Khaira Arby, she’s this wonderful singer from Mali and we listened to a lot of her. It all gets filtered through what Tune-Yards is – a really fun and deep project for me and Nate.”

This deepness is reflected in some of the darker themes explored on the record, including ‘Stop That Man’ which alludes to George Zimmerman – the murderer of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin who was widely regarded as unfairly acquitted. It was also a dark period in Merrill’s life. “There was a lot of self-doubt, a lot of looking at myself honestly and without the lens of success and people applauding for you every night. I was really burned out at the end of the last touring cycle and scared. I think that’s where most of my dark feelings come from, feeling scared. The things that we often do to get rid of fear are often so self-destructive – turning away from reality and from life and wanting to step away from our real lives. Watching myself do that and watching what I saw made me want to really get honest with myself about my behaviours and how I could grow as a person – growing as a person as well as a musician is really important to me.”

She stops for a second, laughing to herself. “I could go on but you’re not my therapist.” Success is not always everything it’s made out to be and she makes a clear point of trying to stay away from getting comfortable with it. “Having that kind of success, it’s not like I’m Lady Gaga but for me, having that new notoriety – it can really fuck with your head and I wanted to stay grounded and humble, in reality. Not in a fantasy that I’m going to be able to afford every health food that I could ever want and houses in the Hollywood hills. This is still a job, it’s still very hard work and it may not be what I want long term. I have to think, ‘What do I want out of music? What do I want out of my career? And what do I want out of this band?’ At the end of the day, this is just work.”

Hip-hop is a particular love of hers and she name checks The Roots, Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean as artists she admires. She also acknowledges that it’s very much part of the lifestyle that she herself doesn’t want to become too enwrapped in. “All successful music gets commercialised. Tune-Yards is getting commercialised and at some point, I might wish for an album to not get critically praised. I want to keep making music that has depth too and I think it’s hard to write over decades. There’s always a danger of getting watered down and that’s why I wanted to travel to Haiti and study a music I’d never studied before, because I wanted to deepen my own sense of what’s possible and not do what every other band is doing right now.”

For ‘Nikki Nack’, they brought in big pop producers in the form of Malay (Frank Ocean, Angel Haze, Big Boi) and John Hill (Shakira, Rihanna, M.I.A) – which was a decision Merrill was very unsure about because she loves to be in complete creative control, but it was an experience that turned out better than she could have hoped for. “Malay worked on ‘Hey Life’ and ‘Wait For A Minute’ and it was a beautiful lesson in production. What he showed is that we didn’t need much more than we already had. He worked his magic with creating some very nuanced sounds that you can barely hear. They’re atmospheric with these really simple touches. He created this full sound. It was only on a handful of these tracks and they were so respectful of what Tune-Yards already was, respectful of each song. They’d be like, ‘Okay, this song is great already – how about we exercise this kick drum?’ It was more that they brought out the good in any song and cleaned it up, simplified things.”

“To me, a lot of the album is thematically about eating the future of our future generations.”

The album was recorded in various places, including a studio in Oakland and in the desert – it reflects the wide variety of influences on ‘Nikki Nack’ and although it was a challenge, it was the most straightforward recording of a Tune-Yards album. “The whole process was rather chaotic, it felt like ‘What are we doing?’ I think now I understand that’s the nature of a Tune-Yards album, it’s very patchwork-y. I don’t know if you’d call it normal but we wrote songs, we wrote some demos, we went into a studio for two weeks so we just do the whole thing and then we mixed it. It’s never been so straight forward and I think the reason for that is that it took place in the editing. There was a whole lot of amazing variety; it was up to me a lot to make sure that the album as a whole feels like it’s a cohesive album. That’s where I’m the producer, I really need to make sure that the vision is clear and that it feels focused.”

A song in particular that feels very different and sounds like a nightmarish children’s bedtime story is ‘Why Do We Dine On The Tots?’ It was rooted in a puppet show that Merrill created in her 20s. “It was based on the Jonathan Swift essay Modest Proposal, a satire about eating babies as a solution for poverty and hunger. I discovered it in a journal, rifling through for ideas I might’ve possibly had years ago. It seemed to really ring true, maybe I’m getting more comfortable with making an album like ones I grew up with – one that not only has music but that has some kind of world to it.” The themes on ‘Nikki Nack’ stem from this idea and Merrill finishes with a confirmation of that, “To me, a lot of the album is thematically about eating the future of our future generations.”

Read More

Tune-Yards - sketchy.

4 Stars

Frenetic and fizzy.

25th March 2021, 7:58am

Tune-Yards share new single ‘nowhere, man’

It's their first new music since 2018!

22nd September 2020, 12:00am

Tune-Yards’ Nate Brenner shares new single via solo project Naytronix

'Human' is the first track from Naytronix’s upcoming album, 'Air'.

7th February 2019, 12:00am

St. Vincent, Chemical Brothers, Reykjavíkurdætur and more make Slovakia’s Pohoda Festival a leftfield gem

Ride, Tune-Yards and Confidence Man were among the weekend's other top-hitters

7th November 2018, 12:00am

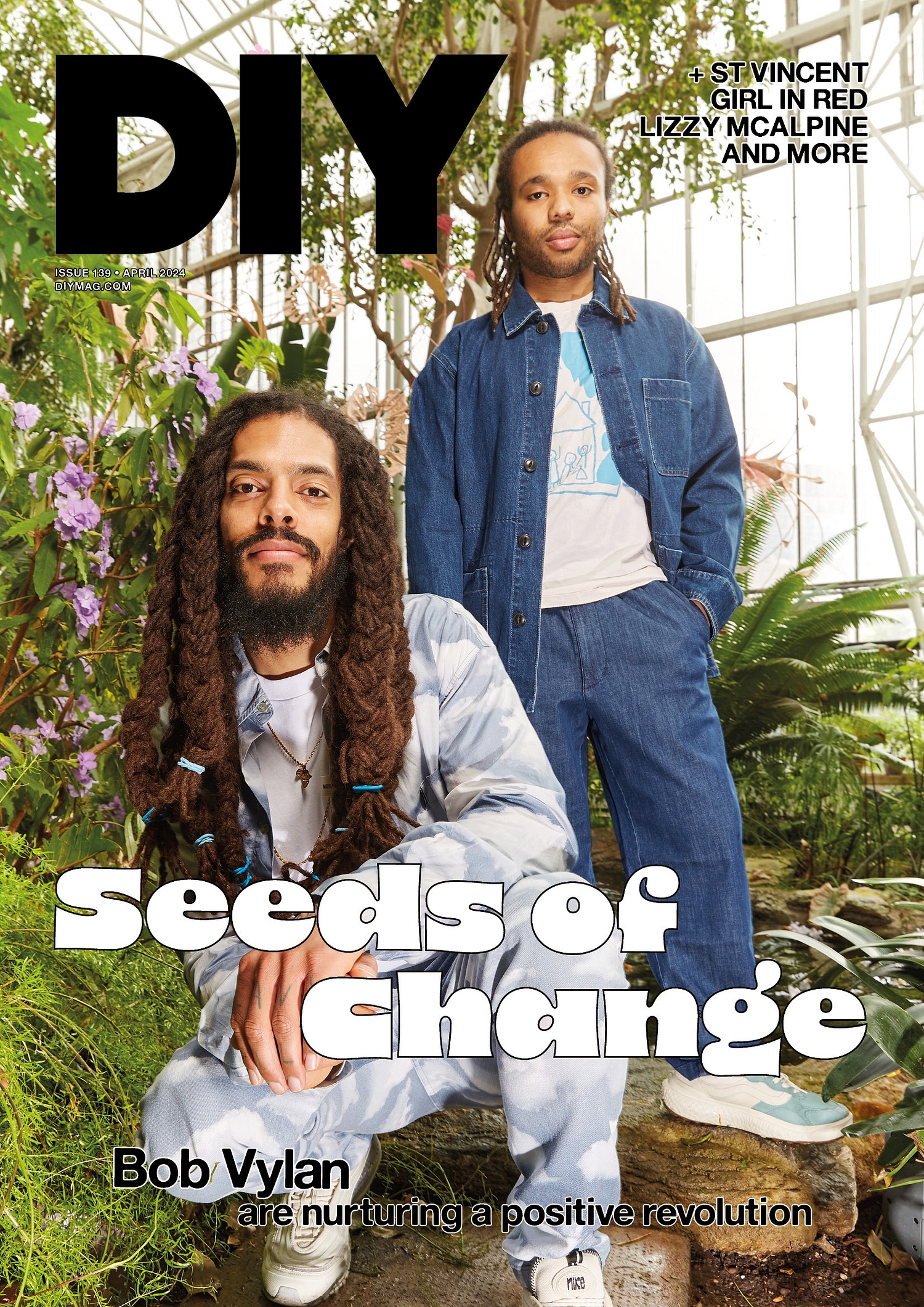

With Bob Vylan, St Vincent, girl in red, Lizzy McAlpine and more.