This isn’t about gender. Except it is.

Women in bands are not ‘a thing’. Lindsey Troy and Julie Edwards are not ‘women in music’. Deap Vally is not a ‘girl band’. Women have proven again and again that we can shred (Exhibit A: Marnie Stern), or growl and roar our guts out like any man can (B: Eva Spence). In any case, a band is about the noises coming through the speakers, not whether the person making them has a penis or not.

“The thing about Deap Vally,” drummer Julie, sat on a sofa in a chilly west London studio, explains, “is inherently we’re feminists. We can’t help it, because we live in a woman’s world with a woman’s point of view. There’s no man involved.” Yet Deap Vally are still forced to battle suspicion that there’s a man plotting their every move. “We haven’t had it a lot, [but] one time, in a review it said ‘I sincerely hope that these girls are doing it themselves, and that there isn’t some mastermind behind them’. It’s disgusting. Let’s get the fuck past that.”

Guitarist Lindsey, unsurprisingly, pulls no punches either. “It comes down to the stereotype that goes along with women dressing skanky. People see women in short shorts and platforms and a lot of make up and the immediate assumption everyone wants to come to is that you’re just a dumb whore.”

Today, Lindsey is sporting tiny velour hotpants with tights and a leather jacket. Julie has trousers on. Both are displaying their midriff. In Deap Vally’s world, that’s a lot of clothing. But it’s not an invitation. And like everything else, it’s a deliberate statement.’It’s not buttoned-up music’ “We never thought it would be as controversial as it is,” admits Julie, “that seems really silly to us. But we’ve faced a lifetime of butts and thighs, and at some point you want to just, like, take it back.

“We want to be strong and we want to be fearless, and dressing that way is part of it. We’re not afraid of what people are going to say.”

“It’s the assumption that’s the most frustrating,” continues Lindsey, “that because we’re dressed this way, we’re trying to appeal to male fantasy.”

“There’s also a double-standard,” Julie interjects. “Some skinny little waif can wear tiny shorts and look like she’s just chilled and relaxed, and I wear tiny shorts and look like I’m a hooker? That’s just the body I was given. Why don’t I have the right to wear tiny shorts?”

“We’re having fun,” Lindsey offers. “The whole idea of rock ‘n’ roll is to have fun, and be over the top, and be flamboyant. It’s like a heightened reality. We play hedonistic music, the whole vibe of Deap Vally is hedonism. It’s not buttoned-up music.”

In the stereotypical canon of rock music, woman is typically painted as prey, fantasy, damsel or victim. Deap Vally’s woman is not. To suggest they’re flipping things completely on their head would be an overstatement, but society still seems so predisposed to the masculinity of rock ‘n’ roll that it’s impossible to finish listening to ‘Sistrionix’ without sporting a massive grin. “You’ve got the hands to touch a thousand hips,” snarls Lindsey on ‘Your Love’, a nod to the male gaze with a knowing wink. Songs like ‘Woman Of Intention’ and ‘Gonna Make My Own Money’; the literal hands-off message of ‘Raw Material’; the stalker-ish recollections of ‘Creeplife’.

The album was recorded in the pair’s home town of Los Angeles. “I think it was good,” Lindsey says, “for the first album especially, to record it at home.” They worked with producer Lars Stalfors, who, the pair state, “has a knack for making it sound live.” It isn’t live, of course, but over its eleven tracks does maintain the whirlwind of energy, the force and ferocity that is Deap Vally.

“We’d track everything in the room at once,” Julie explains, “because we wanted to have some bleed and some imperfections. It’s funny to try for that; the tendency nowadays is to clean up everything just because you can. We really wanted all the crap in there. To me, a record that’s all perfect and cleaned up has no context. It doesn’t exist anywhere. I don’t get it. What is it about? It’s just a song in a vacuum, it’s meaningless.”

And, she adds, none of her or Lindsey’s favourites are polished, either. “Like Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ ‘Fever To Tell’ or Led Zeppelin, it’s raw, it’s not perfect. That’s not the point. I think all studio engineers should hear that loud and clear! There’s something more important than perfection. There’s expression.”

Neither Lindsey or Julie grew up listening to rock ‘n’ roll, and while there’s no rule dictating that records can only be made in the style of those owned pre-puberty, the grandeur, excess and pure emotion of blues-rock is so ingrained in ‘Sistrionix’, it’s still a surprise. Because while Lindsey was avoiding 90s R&B (“I didn’t relate to it at all, it’s not the world I came from… I had a Doors album, then Hole and Nirvana, then ‘Californication’”) and fighting with school friends over Titanic star Leonardo DiCaprio (“he wasn’t aware of it, but we were”), Julie was… what?

“I was a weird and sheltered nerd,” she says, in a manner as close to sheepish as Deap Vally get. “I listened to classical music and musical theatre. I wasn’t ‘with it’, I was in my own world,” she laughs. “When I was, like, 12 or 13, my brother gave me Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side Of The Moon’ and it literally scared me. ‘It’s Raw, it’s not perfect, that’s not the point.’I hated the saxophone bits in it. He gave me My Bloody Valentine’s ‘Loveless’, and I remember being like ‘this is weird’, and then suddenly falling totally in love with it, realising that I was disgusted by musical theatre. I just didn’t know! Nobody had shown me the light.”

“In high school you listened to Nine Inch Nails, though,” Lindsey butts in to point out.

“Yeah, but that was like, later years. Then I got way in to 90s rock, grunge. I love heavy music, probably because it’s the opposite of musical theatre; it’s visceral and cathartic.”

It’s impossible post-00s to mention the words ‘blues’ and ‘rock’ and not follow them somewhere soon with ‘Jack’ and ‘Meg’. More so if you also happen to be discussing a two-piece. There are moments in ‘Sistrionix’ where it’s equally as hard to avoid imagining what it’d sound like with the production skills of Third Man. And many others where Lindsey’s glitchy, rough, guitar noises echo Nashville’s new king pin. It’s not exactly a shock to find out the pair are big fans.

“The White Stripes were killer,” Julie says. “My brother’s band, Autolux, played a few shows with The White Stripes in New York and I went back in like, 2003 or 2004, and I was just so blown away by Jack White. I was just like, ‘WOW’. He’s such an incredible performer, he’s so commanding, he has so much talent. He’s so willing to take risks, and in The White Stripes he was supreme.”

“As a teenager,” Lindsey says, putting the Stripes’ influence in context, “when there started to be that resurgence, I think at the time it was referred to as retro-rock? That was one of the first times I felt really excited about what was happening in contemporary music.”

“There’s a radio station in LA called KROQ,” Julie continues, “and they’d basically been playing the worst garbage imaginable for so long, and all of a sudden there was this renaissance of actually listenable, cool music on there. I think there are so many more female drummers now than ever. We totally have Meg to thank for that.”

Does the same stand elsewhere? At one level, it would appear not. The line-up for this year’s Reading & Leeds Festival, just one barometer of what’s currently popular in mainstream rock/alternative circles, features proportionally few women. At the time of press, just three of the weekend’s main stage artists feature permanent female members (The Lumineers, We Are The In Crowd, The Pretty Reckless); Deap Vally’s peers on the BBC / Radio 1 Stage number only Azealia Banks, HAIM and AlunaGeorge.

And Julie’s not sure either. “I don’t know,” she admits. “In the 90s there were so many women tearing it up and tearing it down and speaking their minds. I don’t even feel like that’s happening now.” Lindsey agrees. “It’s different. There are a lot of women in bands, but there’s not that same attitude of rebellion that the 90s had.”

If there is a lack of rebellion in the mainstream however, it stretches further than female musicians. The heir to Billy Bragg’s political songwriting is oft suggested to be Frank Turner; a man who may have written ‘Thatcher Fucked The Kids’ but since then has occasionally appeared to be closer to her progeny in opinion than not. ‘We’ve Faced A Lifetime Of Butts And Thighs’Should, say, Jessie Ware - to use one of the most prominent women in pop right now - speak out politically because of her gender while nobody’s asking the same of collaborators Disclosure?

But there are women speaking out. Grimes’ poignant blog post of a few weeks ago highlighted the discrepancies between how the industry treats her to her male contemporaries. “I’m tired of men who aren’t professional or even accomplished musicians continually offering to ‘help me out’ (without being asked),” she wrote, “as if i did this by accident and i’m gonna flounder without them. or as if the fact that I’m a woman makes me incapable of using technology. I have never seen this kind of thing happen to any of my male peers.”

While Solange took to Twitter to declare, “I find it very disappointing when I am presented as the “face” of my music, or a “vocal muse” when I write or co-write every fucking song. How can one be a “vocal muse” to their own melodies ,story telling, and words they wrote? Sexism in the music industry ain’t nothing new.”

Kate Nash’s re-invention as a Riot Grrrl for the 21st Century also has her visiting schools to get girls to make a racket. “I didn’t want to make it a big deal,” she recently told DIY, “don’t make a big deal out of women being able to be musicians, that’s fucking weird, and so patronising. But, actually, there aren’t that many, so you feel really contradictory.

“People would ask me, ‘do you write your own lyrics?’ But they never ask if I write my music. I was getting really bitter and angry about the way things are now, and there’s nothing I can do to change that. But what I can do is try and change it for another generation. So they don’t grow up even asking each other those kind of questions, they just know that women can be musicians.”

Indeed, as Icona Pop’s Caroline Hjelt explained earlier this year, “It’s very important that girls help each other out and support each other, and lift each other up.” “When you do your thing,” Aino Jawo added, “and you’re happy with what you do, you don’t need to put energy into hate. We’ve come a long way [with feminism], but I see a long way to go.”

To generalise across all females in music is, ultimately, as silly as the behaviour each of the few examples here recount. No male musician is ever claimed to speak for all mankind; why should any one woman? Or two women.

“I think people who like strong women like us,” Julie concludes. “People who don’t want to see women being courageous and bold, they won’t like what we’re doing.”Deap Vally’s debut album ‘Sistrionix’ is out now via Island / Communion Records.

Taken from the July 2013 issue of DIY, available now. For more details click here.

Read More

Deap Vally announce final release, ‘SISTRIONIX 2.0’ and farewell tour

The LA-based duo will put out their last LP - a re-recorded version of their debut - in 2024.

20th September 2023, 1:04pm

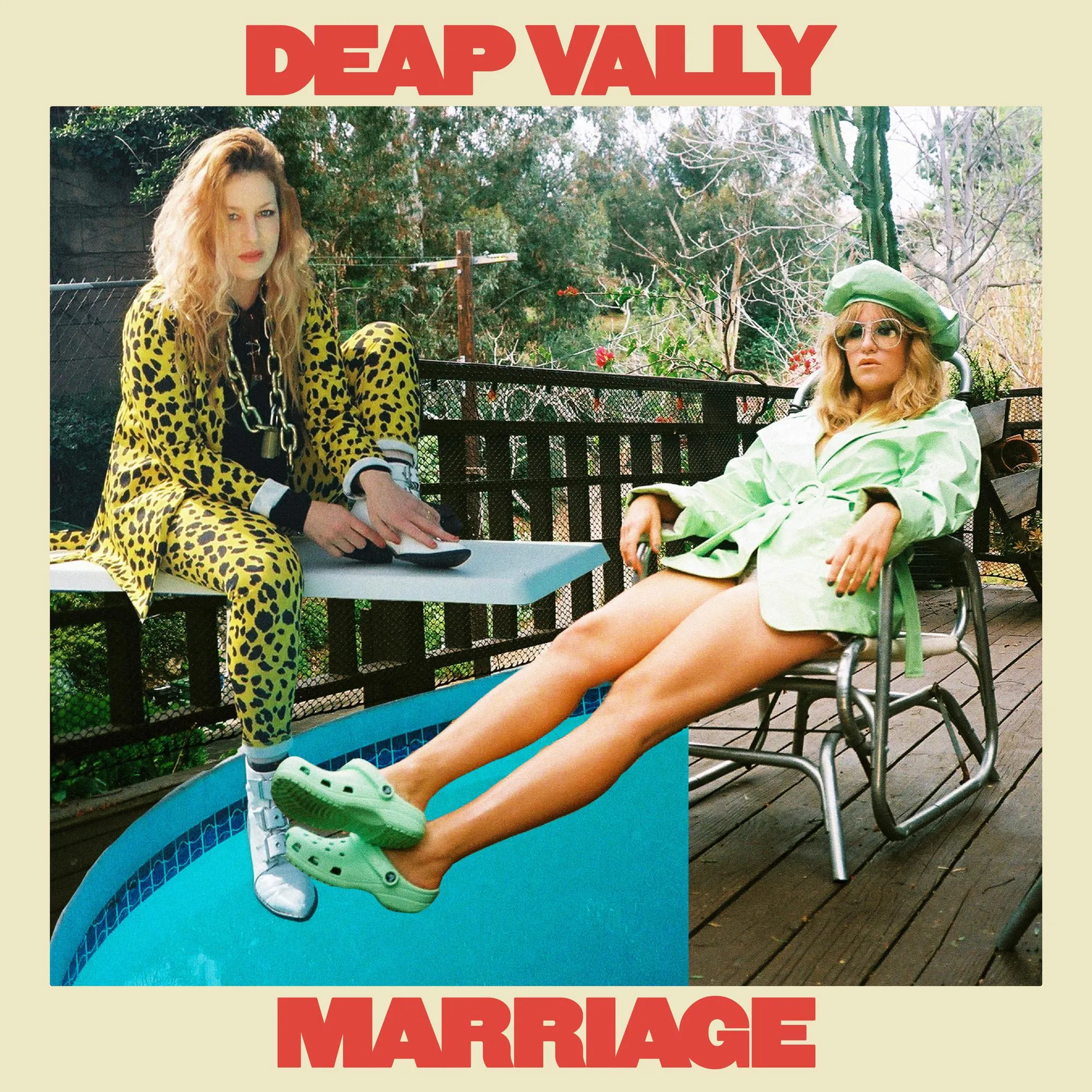

Deap Vally - Marriage

4 Stars

19th November 2021, 12:00am

Deap Vally announce new album ‘Marriage’

The duo's third album is being previewed by their new track 'Magic Medicine'.

6th October 2021, 12:00am

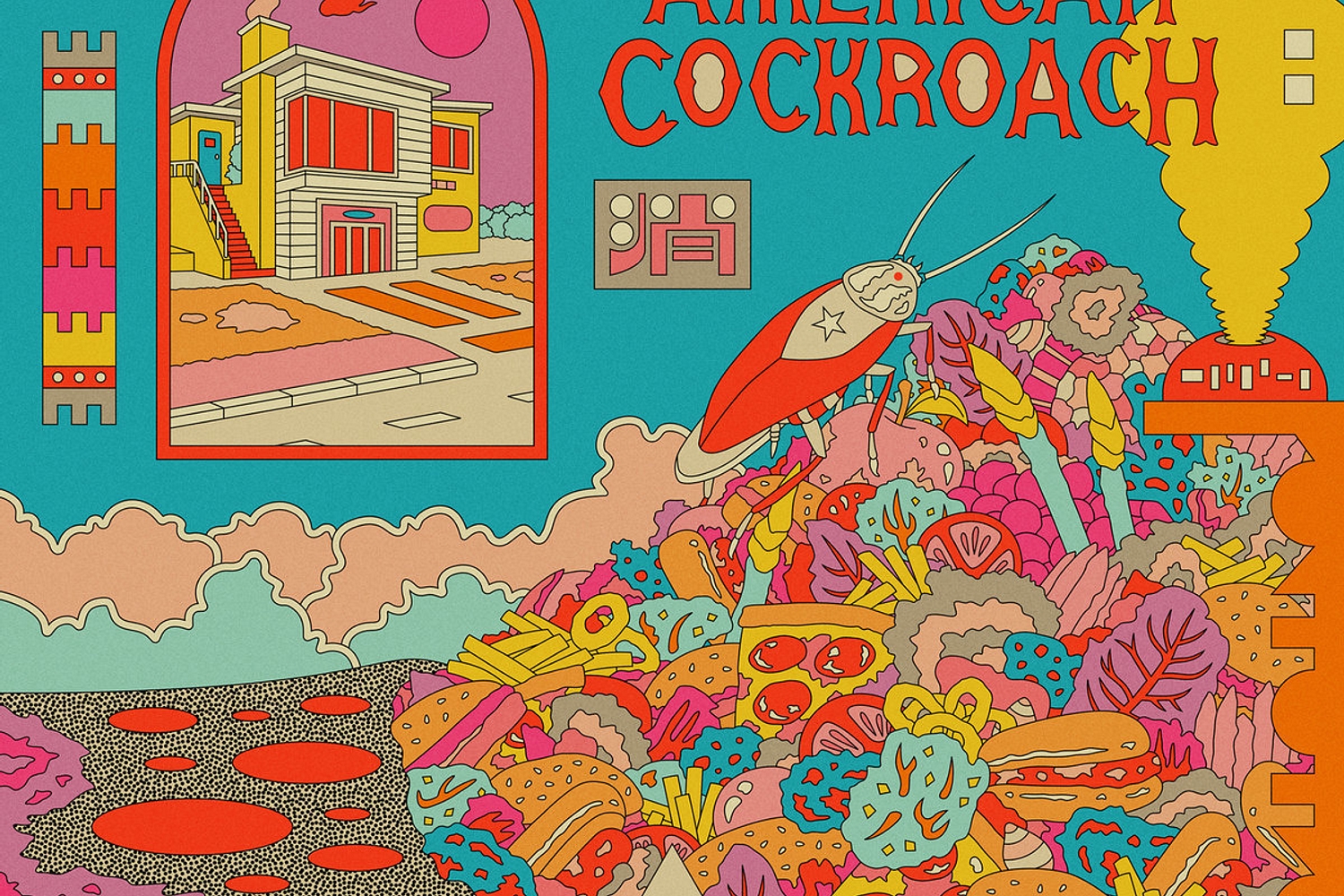

Deap Vally - American Cockroach

4 Stars

This is a triumph.

17th June 2021, 7:57am