Cover Feature Game over? Two Door Cinema Club are back from the brink

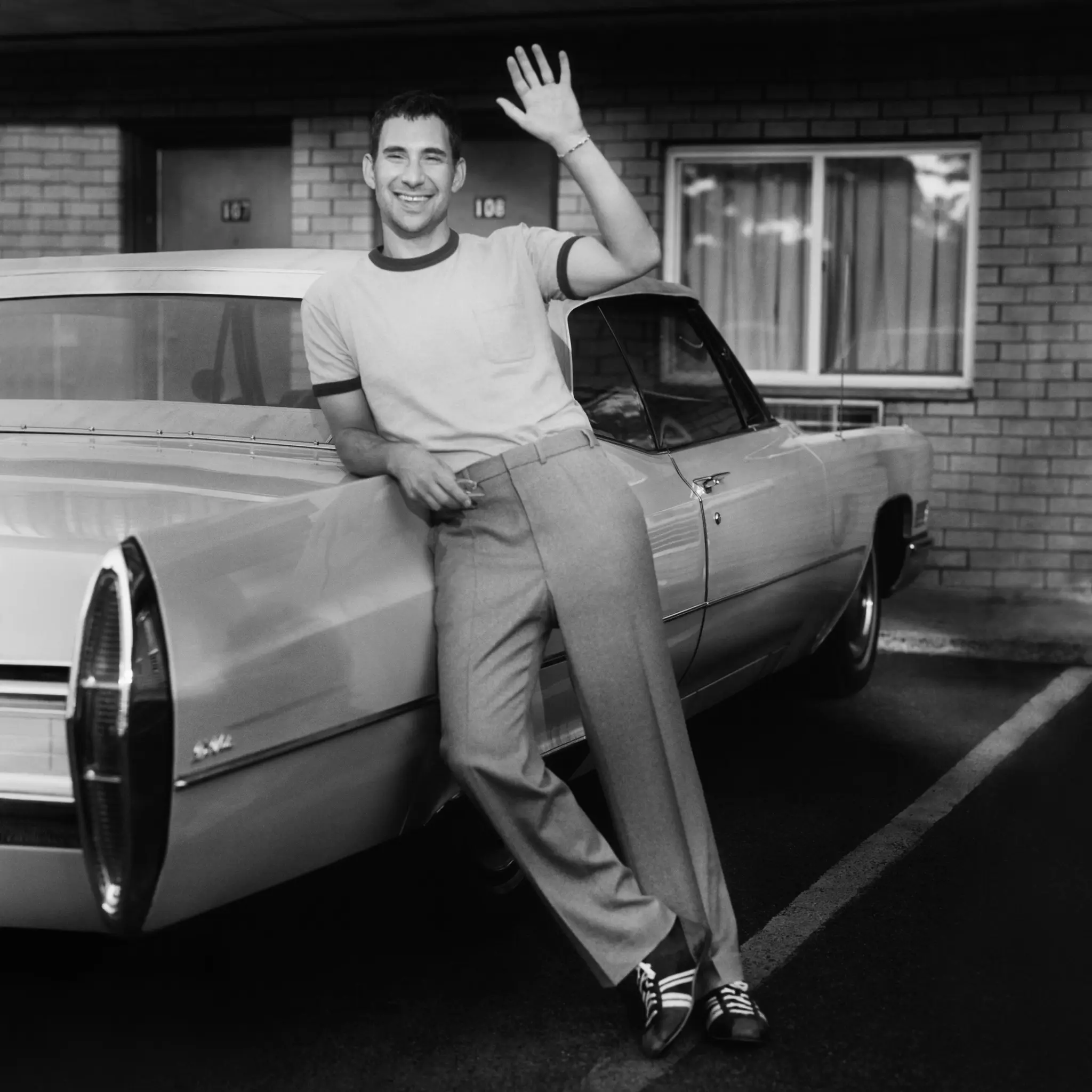

With new album ‘Gameshow’, Two Door Cinema Club are rising from the wreckage.

‘Hiatus’ is a convenient word to use for when bands fancy a break. But for Two Door Cinema Club, they were literally forced to put everything on hold. Hospitalisation, alcoholism and depression cut short all plans and any momentum they’d built in a whirlwind five years. Suddenly, these future headliners had to rethink everything. Now they’re speaking out, addressing creative differences, mental health and how they rediscovered themselves after hitting self-destruct.

Being in a successful band is like sitting in a merry-go-round that never stops. With each chance to sit back and take stock, out steps another opportunity. With increasing demand comes more reasons to book another tour and make a new record. A bigger audience is always out there somewhere. Accolades like the BRITs, Grammys and the Mercury Prize remain unclaimed, so why not strive for all three at once?

Some people are cut out for becoming superstars, capable of maintaining sanity thousands of miles away from home, able to deal with demand from fans and industry alike, press intrusiveness, working with a body clock that’s always out of sync. Others believe they’re dealing with it just fine, but then the cogs and gears begin to tumble.

In June 2014, Two Door Cinema Club were on the brink of headlining their first big UK festival. But their Latitude spot coincided with the band’s breaking point. Frontman Alex Trimble, already in the depths of a nervous breakdown, developed stomach ulcers. He was physically incapable of boarding a plane to go home, and found himself stranded in a Seattle hospital. This came after months of tension within the group. Alex, guitarist Sam Halliday and bassist Kevin Baird weren’t on good terms. Barely speaking, they bottled up disagreements and bit their tongue with the belief that all this hard work would eventually pay off.

They’ve since patched up disagreements, rediscovered friendships and their reasons for being in a band in the first place. But rarely has a group been so willing to inspect their own wounds. The trio are currently in Valencia, Spain, a few hours before a disorienting 1am festival set. “It all came down to ‘momentum’,” says Kevin. “How could we capitalise on all this success that came out of nowhere? We ‘needed to do a new record’, we ‘needed to do this and that’. It’s all about achievement. That new thing where the fee is higher, the slot is bigger, we could bring in more production. It became about status.”

Weeks before their cancelled Latitude slot, Kevin was saying very different things. “Headlining a great festival like Latitude is obviously quite a big deal for us but we also feel like it is the next natural step,” he told the BBC. Everything Two Door said at the time, in fact, referred to being “bigger”, aiming for territory they’d yet to conquer. It’s almost as if they had this sense of achievement wired into their collective mainframe.

As featured in the September 2016 issue of DIY, out now.

Read More

Two Door Cinema Club return with new single ‘Happy Customers’

They've also announced a new string of US tour dates.

7th March 2024, 10:51am

Two Door Cinema Club are back with synth-led single ‘Sure Enough’

The indie stalwarts have also announced new tour dates for the UK and North America.

28th September 2023, 12:30pm

Scouse-Irish solidarity triumphs as Live at Leeds in the Park returns with stellar sets from CMAT, Crawlers and more

The festival's second incarnation is a sweltering celebration.

5th June 2023, 2:09pm

Two Door Cinema Club will play Margate’s Summer Series this year

Tickets to see the Bangor boys will go live on 2nd June at 10am.

26th May 2023, 10:55am