News When Two Tribes Go To War, A Musical’s All That You Can Score

You might be forgiven for thinking that the UK in the eighties was filled with trench coat wearing yuppies, hanging out in trendy wine bars, yelling into ridiculously large mobile phones. You could even subscribe to the ‘Noel Gallagher School of Ill-Conceived Interview Quotes’, that it was all “very colourful and progressive”. You might even think that Thatcher was actually Meryl Streep. Of course, the reality wasn’t actually any of those scenarios, particularly if you were based in a mining community in the north of the country. Less ‘upwardly mobile’, industrial towns north of the Watford Gap and in Wales were literally fighting for their livelihoods, living hand to mouth, desperately trying to stop the singlehanded destruction of their communities by the government of the day.

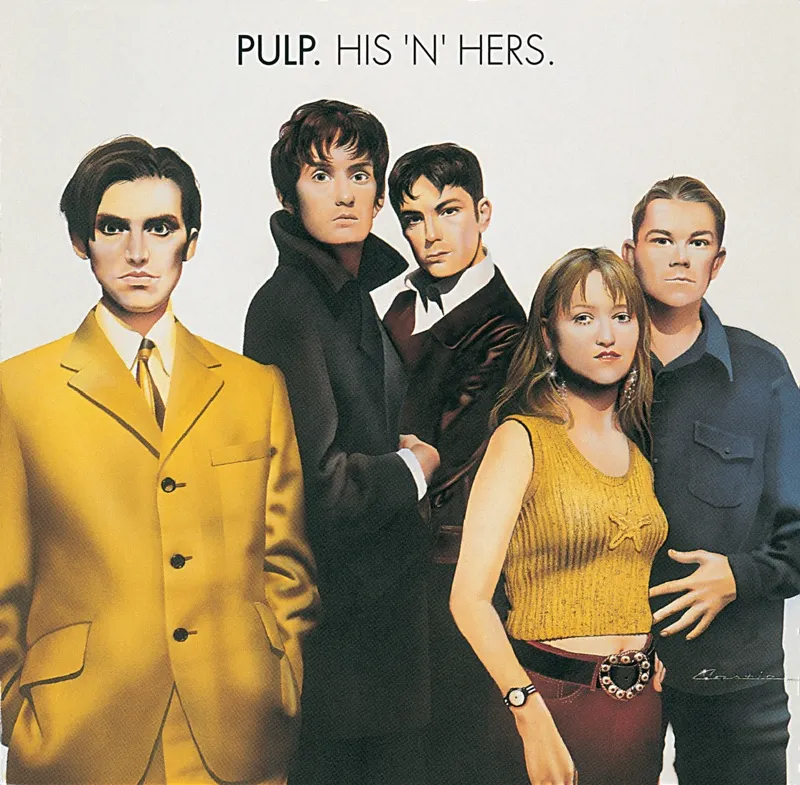

Russell Senior might be best known as a founding member of Pulp, but along with the knowledge of how it feels to headline Glastonbury, he also has hands on experience of what the Miner’s Strike was like to live through. Returning to Sheffield after University, he took an active role in the strikes as a Flying Picket. “Thatcher’s Britain was a savage place and we had seen the steel industry taken apart in a vindictive way,” he tells us, “My father was one of many who had been made redundant and I was unemployed. So when the miner’s strike came along, it seemed like finally someone was standing up for themselves.”

“I heard on the radio that there was a big picket at Orgreave coking plant, so I walked the six miles from my house and witnessed first hand the brutality of the police. But when I went home and watched it on the news, the events of the day had been portrayed in a completely distorted way.

“I went to NUM headquarters on Vicar Lane and basically ‘volunteered’. It was a hotbed of activity and these big characters like Mick McGarthy (the Scottish miner’s leader) and Dennis Skinner were there. Nobody asked me for any credentials, so basically I blagged my way backstage into the situation room of the miner’s strike. And they were open friendly characters, not above exchanging a few words with a young lad.

“There was a big demo in Mansfield and they took me on the NUM bus sat behind Arthur Scargill. So I got something of a birds-eye view and was lucky enough to be at quite a number of the key demos and meetings during the strike, even accidentally ending up stood on the podium at one. And the miners were just open and friendly. I was just a kid tagging along, I don’t suppose I was really supposed to be there but nobody asked me to bugger off, probably assumed that I had some function. Later on I was one a group of radicals who went out in the middle of the night on ‘flying pickets’ and saw the kind of stuff that went on when there were no cameras there. So during the strike there was no week in which I wasn’t a witness to some of the key events including, the very poignant and dignified march back to work.”

As a witness to the reality of the strikes, those events have clearly stuck with Senior, however almost thirty years on, Russell’s choice of media to convey the events might seem a little offbeat. Together with Ralph Razor, who’s initial idea was the inspiration for the project, the Miner’s Strike now sits alongside such subjects as the music of Abba and Queen as an all singing, all dancing, bona fide musical. Unconvinced? You aren’t alone, initially, neither was Senior.

“It started off as one of those ‘crazy ideas that might just work’.” Ralph says, “I liked the playful juxtaposition of the industrial grittiness with throwaway pop hits, but when I thought about it, I realised that the strike was a very dramatic time in history and it has a real revolutionary glamour about it. I mentioned it to a few friends who seemed to think that it could work, and they encouraged me to give it a go. I decided to approach Russell to see if he was interested in a collaboration, as I was aware that he had been active during the strike, and also I figured that his time spent as a musician wouldn’t do any harm either. I sent him an email briefly outlining the idea and his reply was, “This is a ridiculous idea, and I want no part of it”. He later relented and told me that “the sheer absurdity of the idea has won me over’” and he offered to meet up for a chat so that he could act as a “sceptical sounding board for the ideas… to save me making a complete fool of myself”.”

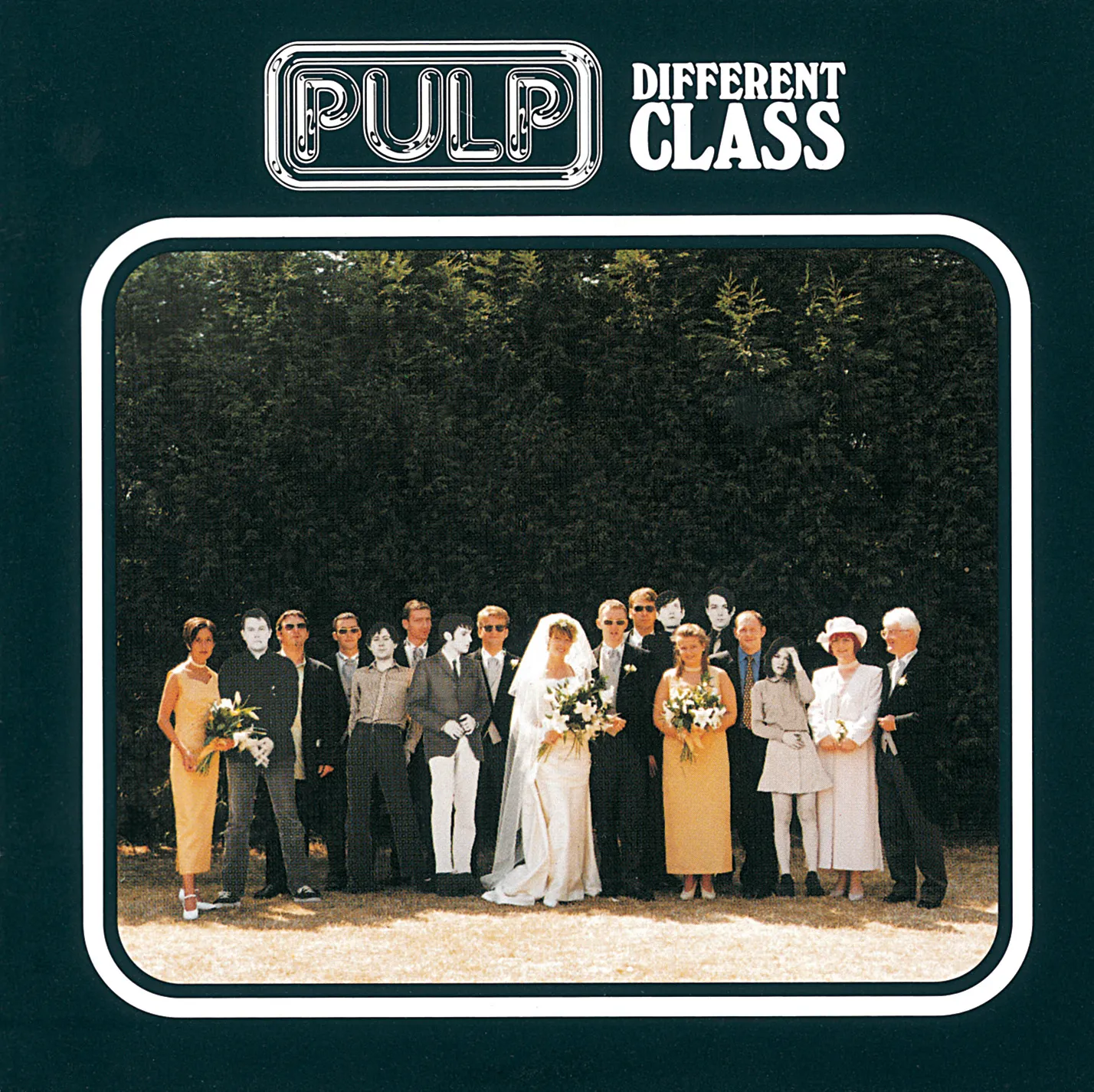

Within a couple of months, a draft of the first act was ready, but with the reformation of Pulp last year, the aptly christened ‘Two Tribes’ had to take a bit of a backseat for a while. “Going back to my old job took a year out of the play,” Senior tells us, “but now I’m back on it full-time.” Just in time, it seems, as the world premiere, or at least an act of the play, will be taking place at this year’s Tramlines Festival in Sheffield – as Senior jokes, it’s now “full steam ahead”. And whilst the musical’s natural home might be in north, hopes are high that the show will tour further afield; “Sheffield is a great place to launch it. For a start, we are based here, and secondly the surrounding area is so steeped in the history of the strike it wouldn’t feel right to debut it elsewhere.” Ralph concurs, “However from there, we plan to take it as far as it can go; I suppose the dream would be to take it on tour, do the West End, Broadway and then turn it into a film or a TV mini-series.”

Whilst the production is very much, as Russell describes it, “a local play for local people”, our hopes of seeing Alex Turner donning a red wig and making jazz hands are systematically dashed by Ralph. “We’re trying to avoid the cheesy cameos at this stage,” he confirms, “so we won’t be trying to get Phil Oakey into a donkey jacket, or drafting in former members of Menswe@r to be extras in the battle of Orgreave”. There’s still hope that Scargill will burst into song though, as we’re warned by Senior to be “careful what you wish for…”

Combining the events of the strikes with the popular hits of the day comes with it’s own constraints; whilst we’d all like to believe that Joy Division and The Smiths soundtracked the life of the average man, the truth is that the mass populous was more likely to be found whistling the Birdie Song and slow dancing to the strains of Renee and Renato (ask your Dad). Keeping with the ‘everyman’ theme might have provided it’s own challenges, as Senior tells us he “hates all the songs in the play”, but it’s not a view shared by Ralph, who states that keeping to the period aesthetic has “made it easier. All the songs that we have included would have been in the public domain at the point in which the scene takes place, so if a scene takes place in March 1984, we can use songs from that month, the month before, the year before, but not from anytime after that point. Certain tracks have been discarded, or not used for a particular scene, on that basis.” This attention to detail would directly lead our new favourite playwrights to the surprising inclusion of Black Lace on the soundtrack. “‘Agadoo’ was a massive hit in 1984, and would have been played at pretty much every single Working Mens Club party across the land that year, so it makes perfect sense to include it, although the scene in which we use it is possibly the darkest scene of the entire play. We don’t want to give the game away too much, but there is a scene in which four miners in the shower sing ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’.”

If all this leads you to fear that the subject matter is being treated lightly in any way, you can rest assured, that absolutely will not be the case. Perhaps we’ve never needed to consider the events of that period more – with high unemployment, public sector cuts, and the country in a deep recession, and the need to fully understand the implications of the strike was one of main motivations of both Razor and Senior. As Ralph says, “when Thatcher gets the Hollywood treatment, you know it’s the right time to launch an independent home grown drama about the Miner’s Strike…”. As we find ourselves in a similar economical and political climate, it’s only with a bit of distance that we can truly begin to evaluate our history; “Chairman Mao was once asked what he thought about the French Revolution,” Ralph considers, “his reply was that it was too early to tell.”

“At the time of embarking, it seemed like it might be a bit of a bit of a hard sell,” Senior admits, “but in a post-kettling world, a lot of young people will find it something they can relate to. The time feels very right.”

For more details on Two Tribes, visit their official website.

Read More

Flow Festival Helsinki adds Aurora, Halsey, Janelle Monáe and more to 2024 lineup

They'll join the likes of Pulp, Fred again.., The Smile and Jessie Ware in Finland this August.

23rd April 2024, 9:00am

Pulp announce first shows in US and Canada for over a decade

The encore continues!

19th March 2024, 11:13am

Flow Festival will celebrate 20th anniversary with Pulp, Fred Again.., PJ Harvey and more

Founded in 2004, the Helsinki weekender takes place on the site of an old power plant.

22nd November 2023, 11:43am

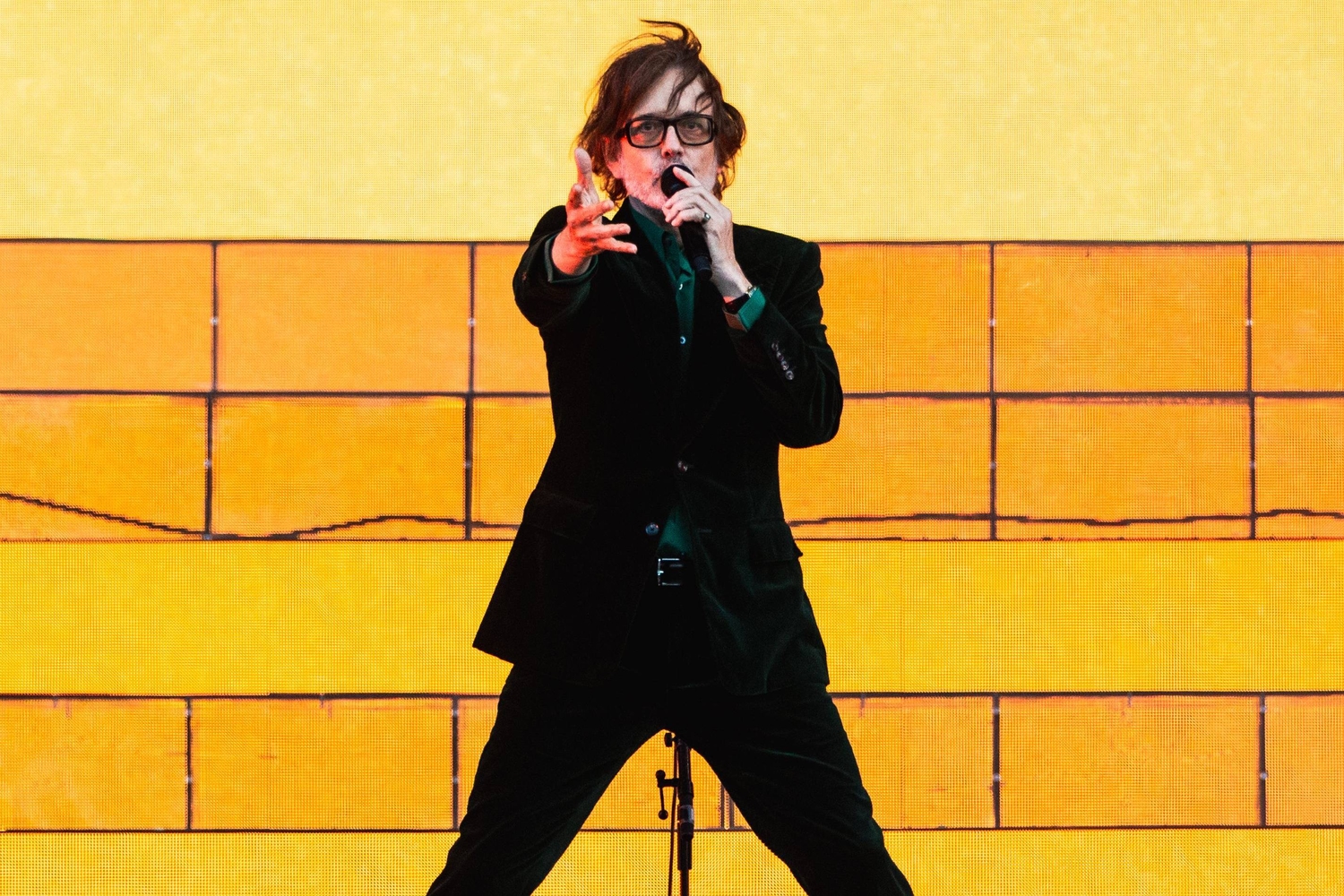

Pulp cement their legacy as one-of-a-kind national treasures at Finsbury Park

With Wet Leg and Baxter Dury in support, it’s an evening of idiosyncratic joy on offer.

6th July 2023, 11:09am

Featuring SOFT PLAY, Corinne Bailey Rae, 86TVs, English Teacher and more!