Interview Death Cab For Cutie: “I want us to be the best version of what we are”

Death Cab For Cutie frontman Ben Gibbard contemplates the pandemic fuelled existentialism in the band’s tenth album, ‘Asphalt Meadows’.

Mortality has never strayed far from Death Cab For Cutie frontman Ben Gibbard’s mind for long. It’s given him plenty of inspiration over his band’s near two-and-a-half decades of activity, and lent their music the sense of fragility and emotion that’s given them this longevity.

At the tail end of the band’s touring cycle for their 2018 album ‘Thank You For Today’, COVID took hold of the world and promptly shut it down. With the number of fatalities rising at an alarming rate day by day, death began to feel real in a way it never had. The emotions of the globe that Ben observed as he watched the situation evolve were then channeled into Death Cab’s delicate, contemplative tenth album, “Asphalt Meadows’, part of which was pieced together remotely.

Now, on the eve of its release, we speak to Ben about how that process shaped what that album became, how his thoughts on mortality have evolved and the legacy his band has built.

How and when did you begin laying the groundwork for “Asphalt Meadows’?

I tend to start sketching ideas for new songs in the months after the previous record comes out. So in this case, it started while we were touring a lot in 2018-2019 but, of course, some events got in the way. As with every record we’ve made, I end up writing as much as possible and hopefully, by the time we go into the studio, we’ve got a lot of material to choose from. With this particular record, starting in lockdown, the band started writing together in a way that we never had before. So that kind of added a whole other batch of material to the stuff we could choose from.

In what way was it different?

A couple months into lockdown, I came up with this idea. On a Monday, Zac [Rae, keyboardist/guitar] might create a piece of music, a piano piece or guitar piece, and upload it to a Dropbox. On Tuesday, let’s say, Nick [Harmer] would add bass to it and upload it, and then on Wednesday, I would download it, add a melody and lyrics, and so on and so forth on Friday, where everybody had contributed and we had some semblance of a finished demo. But the rule that we came up with was that you only had 24 hours with the music, so you had to get your stuff done in a timely fashion - kind of first thought, best thought. Also, while you had the music, you had full editorial control over it. So if you didn’t like something, you could remove it, if you didn’t like the tempo, you could change it, and so on and so forth. So, you know, we kind of started this being like, “Let’s just see if this kind of bears any fruit,’ and very quickly, we realised that it was taking us all into some areas that we hitherto had not been able to go, or I had not been able to go as a songwriter, because usually when I’m writing songs, I’m starting from scratch and creating a guitar or a piano part, or whatever it might be, and then writing a song and passing it on to the band. But in this case, you know, if a piece of music starts with Zach, he’s got very different harmonic tendencies than I do so he might inspire a melody or a lyric that wouldn’t be something that I normally write on my own if I’d started the piece. It didn’t always work, of course, but a little more than a third of the record came from that style of writing.

This record deals a lot with mortality and the fragility of life, topics that have often come up in your work. How much have your thoughts on that topic evolved since the early days of Death Cab?

I think my feelings about mortality and my particular path in life has. I would say they’ve certainly evolved from when I was in my 20s, because I’m in my mid-40s. In my 20s, I had a lot more of my life in front of me and I was fortunate enough to not to have any friends die at a young age. But, you know, now in my mid-40s, I’ve had a number of friends die. My feelings about whatever exists after this mortal coil that we’re on have shifted, and I’ve become more introspective about it, because I wonder if I’m ever gonna see these people again, in any form or fashion. Mortality feels like much more of a lived experience at this point than it did when I was in my 20s, so I think I’m just writing about it a little bit differently. I think [when I was] writing about mortality when I was younger, it was certainly a little more conceptual.

In your music, what do you get out of exploring topics as existential as the ones that you’re contemplating on this record?

I feel it’s just kind of an open conversation. These are things that everybody experiences. I mean, I think most people - unless you’re in a fundamentalist sect of some religion - we’re all asking a lot of the same questions, I think. What I get out of it is the catharsis of stewing in it, and asking myself the questions in public, that I feel a lot of other people ask themselves, and what I hope that other people get out of it is when the songs are played live, they’re relating to some of the subject matter and the uncertainty that we all experience in life, so that they feel like they’re not alone. I feel less alone, when I’m able to express these kinds of feelings and doubts in front of an audience.

What inspired the title choice?

I really liked those two words together. When you think of a meadow, at least most people would think of a peaceful, beautiful place or thing. But we talk about cities as being very beautiful as well - we talk about how beautiful Paris is, or London or New York. I enjoyed ruminating on the idea of the beauty of a completely manmade environment. A city is basically: in a sense, a city is humankind’s domination of nature, right? I mean, there are, obviously, not a lot of photos, of course, but if you bought a drawing or painting of what New York or Manhattan was like before; before it was what we know now and it was just a wooded Island: but in the kind of development of cities around the world, you know, we’ve started to think of cities as being beautiful places. I like the idea [that] if you’re high up in a building over a city or you’re flying over a city, a city feels as peaceful as a meadow, because you don’t get a sense of the chaos there.

What sort of place do you feel like Death Cab has in the music world in 2022?

I think we kind of see ourselves as - if I could be so bold - a little bit like elder statesmen. I’m a lifer, we’re [all] lifers; this is what we do for a living. I mean, I think about our legacy every once in a while, but I want us to be the best version of what we are and what we have been as long as humanly possible. We’re very fortunate that our music has impacted a lot of people and people are still coming to the shows, they’re still having a good time. And to have been making music as long as we have and to have people showing us this matters to them by coming to the shows messaging us and singing along and whatever else, you know, it makes us feel like it’s not so much that there’s another mountain to climb as much as it is that that we maintain the one that we’re on.

'Asphalt Meadows' is out now.

As featured in the September 2022 issue of DIY, out now.

Read More

Gossip, Phoenix, Sleater-Kinney and more to play All Points East 2024

They're part of the just-announced full lineup joining The Postal Service and Death Cab For Cutie in August.

31st January 2024, 2:30pm

Death Cab For Cutie - Asphalt Meadows

4 Stars

A record that finds its voice in emerging into musical freedoms found in separation.

16th September 2022, 12:00am

Death Cab For Cutie announce UK and European tour

Their new album ‘Asphalt Meadows’ arrives later this month.

2nd September 2022, 9:40pm

Death Cab For Cutie share new track ‘Foxglove Through The Clearcut’

The track gets taken from their forthcoming album ‘Asphalt Meadows’ which is due out next month.

11th August 2022, 9:40am

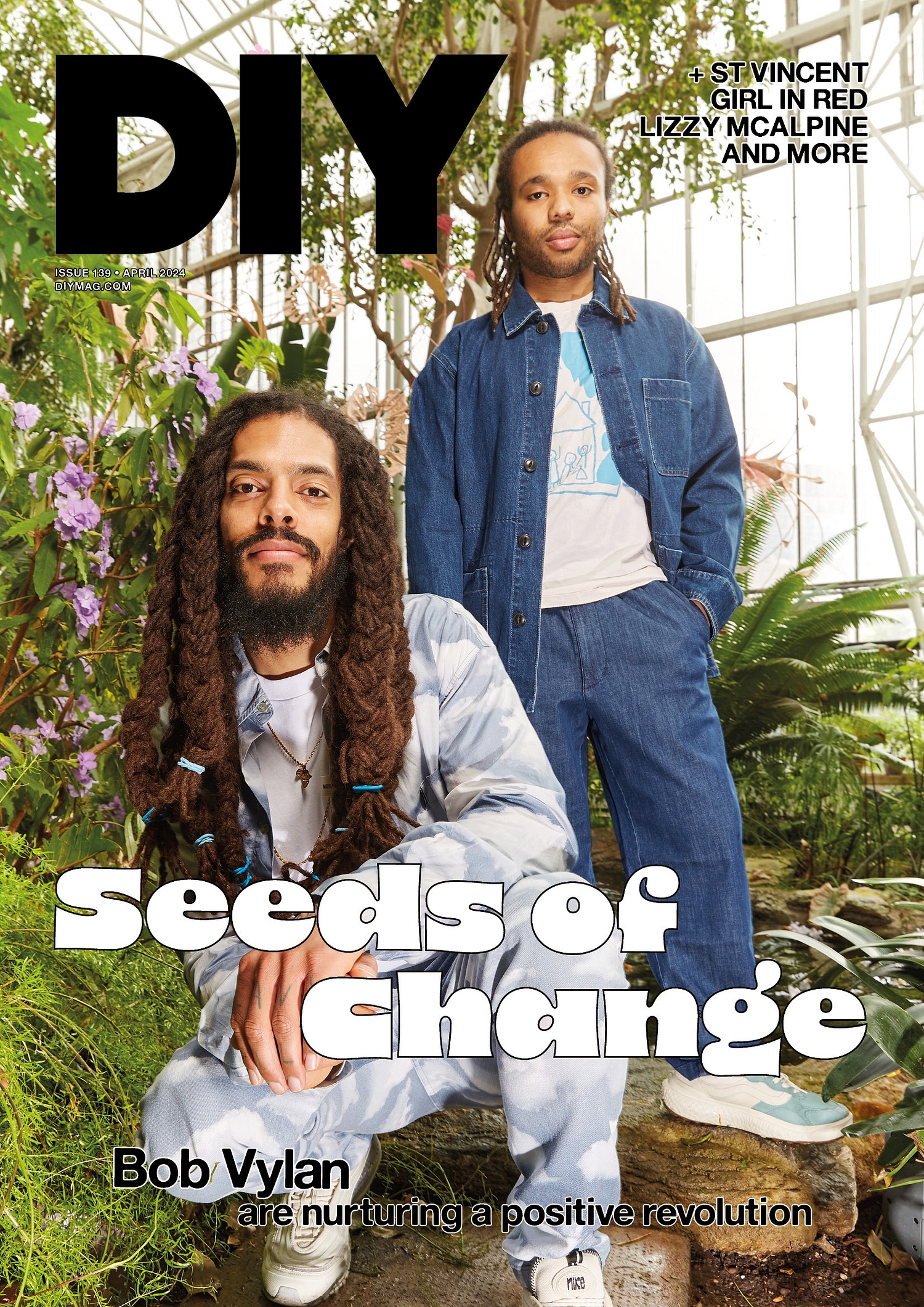

With Bob Vylan, St Vincent, girl in red, Lizzy McAlpine and more.