Interview Borders, belonging and beats: Swet Shop Boys

Swet Shop Boys go for broke and rep their mixed-up identities through a bona fide blend of South Asian influences, UK grime and American hip hop with debut release ‘Cashmere’.

It’s 2016 and borders are everything, and they’re nothing. In one sense, we’re living through a golden age thanks to modern technology, with Skype and FaceTime at our disposal to communicate with anyone on the planet in real time, dissolving physical partitions and rendering timezones mere trifles. But away from the URL and back IRL it’s a different story. The ascendancy of Donald Trump in the US and his controversial, divisive bid for the presidency has made clear what he thinks about borders and who he’d like to keep out of them, from his plans to build a vast wall along the American-Mexican border, to ensuring that Muslims are banned from entering the United States. In case those of us across the pond are feeling smug about these dangerous transatlantic shenanigans, our recent record in the UK is nothing to feel complacent about. The shock of Brexit in June, fuelled by a xenophobic and fear-mongering Leave campaign once and for all exploded the myth that we live in a tolerant, post-racial society. And PM Theresa May, who has previous form with her “go home” vans aimed at illegal immigrants, recently suggested that foreign doctors won’t be welcome here beyond 2025; an ungrateful and inhospitable shove to the 1 in 4 non-British medics who work in service of the NHS.

Talking to the Swet Shop Boys – Riz MC, better known as actor Riz Ahmed, rapper Himanshu ‘Heems’ Suri, and musician/producer Tom ‘Redinho’ Calvert – via the wonders of the three-way conference call, with Heems in Brooklyn, New York and Riz and Tom speaking from South London, borders melt away, even as they’re a theme that runs throughout new album ‘Cashmere’. Cashmere is of course, a type of luxury fabric; when combined with the sly punnery of the group’s name and its nod to South Asia as the garment-producing capital of the world, it becomes a comment on the painful history of colonialism and its links to conspicuous consumption, fuelled by cheap labour. The word itself however comes from an anglicised spelling of Kashmir, the disputed territory between Northern India and Pakistan, and tensions between the two countries have recently been kicked up a notch. An attack on an Indian army camp last month, resulting in nineteen fatalities, has been blamed on Pakistan and is having a sinister knock-on effect on the music and film industry in India, with some organisations attempting to ban Pakistani actors and artistes from working in the country.

At least within the group, there’s nothing but love between Riz and Heems – of British-Pakistani and American-Indian heritage respectively – even if working together on ‘Cashmere’ wasn’t always straightforward. Elaborating on the creative process, Riz explains how “it’s so funny like, sometimes you work with people and you kind of go, ‘oh man, we work exactly the same way, and we see eye to eye the whole time’ and it hasn’t been like that for this… at all. There’s been growing pains of Himanshu doing stuff like ‘BAM! I’ve done my verse’ five minutes in, then a day later I’ll go ‘nah, I’ve rewritten it, I’m gonna change it like this’ – so sometimes there’s been that dissonance: we each have our own clear ideas on how do stuff”. The pair first met in New York in 2012, when Riz visited Jackson Heights in Queens to research his role in much-acclaimed HBO drama ‘The Night Of’. He ended up getting together with Brooklyn-based Himanshu and they quickly realised they had a lot in common. Their first EP followed in 2014. Redinho’s history stretches back further. “I’ve known Riz for a while, we met a long time ago on MySpace and started collaborating together – probably about 10 years ago – and then Riz told me about this project he’d started with Heems called Swet Shop Boys, which I thought for the name alone was great. I wanted to be involved”.

"Swet Shop Boys has been one of the most enriching, creative and collaborative experiences of my life."

— Riz Ahmed

Considering both he and Riz are Londoners, not to mention Riz’s busy schedule in terms of his acting career, and Himanshu’s base is in New York, how did they coordinate recording the album? “Well, I make the music and then it’s simply a question of getting everyone in the room” he explains. “Heems’ style has influenced the process a lot; he likes to shoot from the hip and not hear the beats before he gets into the studio”. Due to the trio’s speedy work ethic they managed to record the majority of the album in five days. Expanding on the process, Riz laughs as he describes how Heems quite literally didn’t skip a beat from disembarking the plane to laying down the final tracks at his flat earlier this summer: “Heems banged out three tracks in like twenty minutes or whatever straight off the plane, and I’m really frustrated thinking ‘shit I don’t want to work that fast!’”.

It’s not only Riz and Heems’ processes that differ – their styles of rapping are fairly disparate. Heems delivery is very laid-back and relies on stream-of-consciousness, whilst Riz’s bars are sharp, smart, and almost scholarly in their citations. Heems jokes in a self-deprecating manner that “a lot of my work process and the reason why it sounds so laid back is sheer laziness”, but goes on to confide that this approach is a form of displacement and the way he deals with coming from a “working-class, South Asian, diasporic background… being a rapper, being an artist and going outside the professional norm is frowned upon. So my way of dealing with that would be to not focus so much on the music and on the writing, which is obviously the bulk of the work, but to focus on other things, like how it would be marketed and occupying myself with the whole process that comes after recording”. He concedes that despite Riz’s similar upbringing, his method is opposed to his, with Riz’s approach being to “pay a lot of attention to how it’s written”. It’s something he really admires: “I’ve always wanted to be someone who perfects their craft, and working with Riz has taught me to take the time to try to do that”. The appreciation is definitely mutual though, as Riz notes how collaborating with Heems has made him “a little bit more playful, more comical, more laid-back with my bars” compared to his solo output, such as on recent mixtape ‘Englistan’, which was only wrapped up a few months before finalising work on their group album.

“I was just trying to put away my ‘Englistan’ headspace of writing a poem-type shit, and really crafting the whole thing… so I was writing a lot at the start and Heems was freestyling”, which he puts partly down to the “the UK/U.S. difference”. It’s easy to hear what he means. While Riz spits his bars with the kind of ruthless flow that seems indebted to the UK grime scene, Heems is more beholden to American rap constructs, heard best on tracks like ‘Swish Swish’ and ‘No Fly List’. On the latter, he points out the semantic absurdity of how, despite his inherent flyness - a classic hip hop trope - he’s on a no-fly list and asks with insulted disbelief, ‘You ain’t flyin’ shit / Why they let you on like a pilot?’, over a bass-heavy beat. However, by the end of the record they’ve almost taken on each others’ voices via a subconscious exchange.

“By the time we’d reached ‘Din-e-iLahi’”, Riz says, “I decided to freestyle my bit – which you can probably tell, it’s not really a rap – and Heems wrote his, so it was quite interesting to me in terms of the journey that had taken place”. When it’s pointed out that there are a few other moments where Himanshu breaks out of his trademark ‘lazy’ style and blasts the mic, such as his blistering, no-holds-barred verse on ‘T5’, Riz becomes animated and reveals his competitive emcee side.“I’ll tell you what yeah, he took all my Muslim words, he stole them!” he protests. “He backed me into a corner with all that ‘inshallah’ and ‘mashallah’ stuff”” Himanshuchuckles in the background. The affection and respect that exists between the two men is palpable, even over the phone, and is probably what prevents the record from turning into an elaborate pissing contest. Riz only confirms this further when he remarks thoughtfully on how “being in Swet Shop Boys has been one of the most enriching, creative and collaborative experiences of my life, despite the total number of days we’ve worked together having been so limited. I’ve learnt and grown so much from it because working with someone who’s got such similar reference points and values as you but who comes at it so differently, shocks you into taking a look at yourself… it’s been cool”

"When you’re marginalised I feel like one outcome is that you begin to get comfortable in the shadows, in the margins.."

— Himanshu Suri,

As might be expected for two artists with a shared, though subtly different, South Asian heritage there’s a wonderful array of instrumentation from the Indian subcontinent on display on ‘Cashmere’, and it’s anything but predictable. ‘Tiger Hologram’ is one of the few songs, if not the only one, where the beats aren’t just on a par with the bars – they overshadow them. Its Qawwali-inspired feel, which has as its focal point a harmonium-synth of Redinho’s own creation, is a particularly special track.

“That was the first beat I made for the album,” Redinho explains. “The handclaps as well, and the kind of feel on that track in particular, it was like ‘how can I create a palette that’s relevant to this project but not overt?’. With a lot of projects that have a crossover with South Asian music it more or less boils down to taking a Bollywood sample and whacking a drum loop underneath it, which is really basic and not very creative,” he observes. It’s clear Redinho has dove in, and done his research when he goes on to illuminate the history of the harmonium and how it’s emblematic of ‘Cashmere’. “For a lot of the Qawwali guys, particularly Aziz Mian, the harmonium is central but it has a controversial history; it was introduced to South Asia by the colonial powers, then at some point it was banned from All India Radio for about 30 years because of that association with imperialism,” he explains. “It was as popular as it is controversial though and has become almost synonymous with South Asia. It functions as a symbol of the identity issues that are at the core of this project”.

Elsewhere, there’s the ghungroo/payal (anklets) that shimmer on ‘Zayn Malik’, the ney flute that wraps around ‘Half Moghul Half Mowgli’ and the piercing wails of shehnai that cut through ‘T5’. Even ‘Aaja’, with its tipsy sitar/tabla combo and obvious Bollywood feel, could have easily gone down the sampling route but eschewed it for a vocal sung sweetly in Urdu by rising Pakistani star, Ali Sethi – a “trained ghazal don” according to Riz – although the lyrics were written by Riz himself. “Basically, I was singing the hook and going ‘this is fun in kind of a punk way, right, right… right Tom?’ and he was like ‘nah, we should get a singer on it’”. Heems cuts in here to point out his sneaky contribution of one line and lets himself in for a ribbing from Riz: “Yeah, your line was about ‘pyasa’ which was [mocking]: ‘oh, mera dil hai pyasa [my heart is thirsty]’. I was like ‘oooooooh, that’s some straight up Bollywood shit, man!’”.

Thinking on Heem’s earlier comment about going against the grain by choosing an artistic career as opposed to a profession, they’ve also been pondering their family’s reactions to their chosen career paths. Riz goes first. “There’s always a similar reaction, which is like: ‘hahn hahn, aapne theek kiya [yes yes, you’ve done well]’…”, he pauses here then abruptly backs up. “Actually, it’s not even that, I’m telling a lie. Why am I polishing it? I’ll tell you how it is – my mum will be like ‘why are you swearing?’, and my dad will say ‘stop doing this leftist baatein [talk]’. My parents basically want me to play it safe and not rock the boat: they get concerned because I say political stuff and they never know what could happen to me as a result. It’s typical of the mindset of the generation that migrated here: there’s this sense of ‘we’re guests here so we should be polite’. Whereas for people like me and you, instead we’re like ‘nah, this is my country and I’ll say what I want’. So there’s always going to be that tension”.

This topic is all the more loaded considering that Riz’s essay from The Good Immigrant was printed in the Guardian the day before this interview, before going viral on social media. According to Riz, the reaction at home was somewhat different. “It went nuts online and I didn’t expect it to get such a nice response but anyway,” he says, “I came home and I was telling my mum and dad about it like ‘did you see it?’, and they weren’t happy. They weren’t being mean about it or anything but they’d really rather I not talk about that kind of stuff. Don’t rock the boat, play it safe, keep your head down – that’s their mentality”. Himanshu interjects here: “when you’re marginalised I feel like one outcome is that you begin to get comfortable in the shadows, in the margins […] and myself, actually being American and identifying as American I’m like ‘why would I hang out in the shadows? Put a spotlight on me!’".

"My parents asked ‘why are you so obsessed with rapping from the inside of the barrel of a gun?’. I just believe that if you have a platform and you have the opportunity it’s important to use that”.

— Himanshu Suri

It starts to become apparent that Himanshu is somewhat fearless, flying to Paris the day after the terrorist attacks in November last year . “The next day I had to get on a flight to go to Paris to rap and my parents wanted me to cancel it,” Himanshu says, “Like, I don’t know if my parents knew that other bands were cancelling stuff, I don’t know if they read Pitchfork that particular morning, but the general consensus was ‘don’t fly to Paris and Belgium to rap’. But being here [in New York] after 9/11 it was really important to me to spread positivity via music to a different city that’s been affected by a similar fate”. And his dancing with danger doesn’t end there. “This year I was like ‘hey ma, I’m gonna go to Palestine to rap!’ [laughs]. My parents asked ‘why are you so obsessed with rapping from the inside of the barrel of a gun?’. I just believe that if you have a platform and you have the opportunity it’s important to use that”.

Spreading love to other countries whether scarred by terrorism, war, or the legacy of colonialism is important to both Riz and Himanshu. When asked to unpack a line on ‘Zayn Malik’ about ‘fresh back off the boat’, Riz offers a correction. “Normally it’s ‘fresh off the boat’ but I’m actually saying ‘nah we’re looking fresh getting back on the boat’. The full line is: ‘fresh back on the boat, I’m like the brown Marcus Garvey’”.

Marcus Garvey was a Jamaican-born black nationalist who was an advocate of Pan-Africanism, urging displaced peoples to return to their ancestral homelands. Of course, Riz is not literally saying diaspora desis should pack up and go ‘home’; for one thing - as Himanshu points out - there’s figuring out where exactly home is.

“If we got on a boat and went back to quote-unquote South Asia, the issue would be: do I go to UP [Uttar Pradesh, a state in Northern India] or Rawalpindi? Does Riz go to Karachi or UP? Which side of the border are we each going back to? So the idea that Marcus Garvey had of going back to Africa is an interesting one, but then you look at the reality of what’s changed there and what’s happened after the things that made us leave, and you go back and of course it’s different. It’s the classic diaspora story”. Riz agrees but also highlights the healing potential of taking the Swet Shop Boys to South Asia.

“One of the dreams of this project is to tour it around South Asia,” he enthuses, “and for me personally, the seed of the dream that started this project is joining up the dots in the diaspora. There’s something very healing about that concept. You feel like you don’t fit in, you’re like a mongrel, and it’s alienating in a lot of ways if you have that cultural contradiction at the heart of your identity – but it can also be enriching. When you go back to India or Pakistan you go ‘oh okay, maybe I’ll connect there’ and then you realise ‘nah, I don’t fit in here at all’. So for me it was seeing other ‘mongrels’ in their own weird parallel universes, like meeting Heems in New York, or going and meeting fifth generation South Asians in Durban in South Africa, and realising that we are all part of this global mongrel family. That felt like more of a homecoming to me than going to Karachi or Mumbai”.

Recognising perhaps that there’s no easy solution to the third culture kid conundrum of displacement, Riz quickly undercuts the discomfort of this realisation with playful irreverence, asserting “the solution is to just chirpse Persian girls in Farsi”. He laughs as he goes on to tell a vaguely aside about how ‘ba man ghave’ (a line from ‘Zayn Malik’) was the first thing he was taught by a “receptionist in Tehran when I was filming Road to Guantanamo there in 2005 which basically means, ‘would you like to have a coffee with me?’”. He goes on to describe Iranian romance rituals: “So, I just want to put it out there that Iran is a super chirpsey place. Everything happens undercover, which makes it all illicit. I remember once we were in an internet café and we saw a guy and a girl sat opposite, blatantly messaging each other on instant messenger! That’s what happens there: all these guys and girls go to internet cafés together and they’re just chirpsing each other via iChat, sat across from each other, and it’s kind of funny”.

With ‘Cashmere’ Swet Shop Boys embrace and celebrate the dualities that lie at the heart of belonging neither here nor there, and urge us all to do the same. Riz speaks with deep pride of the album and its collaborative ethos. “I don’t feel like this is blowing my own horn in a way it would be if I was talking about a solo album – so much of this record is about what these guys have brought to the table and what we’ve achieved together”. He vaguely echoes the soundbite sampled on the album of Malala Yousafzai’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, an award that was also given to Indian Kailash Satyarthi: “I am proud that we can work together, we can work together and show the world that an Indian and a Pakistani, they can work together and achieve their goals”. Maybe it’s a little cheeky, and self-aggrandizing, comparing their teamwork on a hip hop album to decorated Nobel Peace Prize winners but it’s also touching. Along with Redinho, Riz and Himanshu have shown that borders can be erased and redrawn, and home is anywhere that you feel you belong, regardless of where that may be.

Swet Shop Boys debut album ‘Cashmere’ is out now via Customs.

Read More

Riz Ahmed announces new album, ‘The Long Goodbye’

It’s “a breakup album - but with your country”.

27th February 2020, 12:00am

Watch Swet Shop Boys play ‘T5’ on Colbert

Riz and Heems added a couple of extra verses to the ‘Cashmere’ track.

30th June 2017, 12:00am

The best things we saw at Primavera Sound 2017, Day Three

From Arcade Fire's insta-classics, to a secret Haim appearance via Grace Jones' hula-hooping, it's our final day in Barcelona.

6th May 2017, 12:00am

Swet Shop Boys have a new video for ‘Aaja (ft. Ali Sethi)’

Shot around New York, the video follows a poster-paster as he accidentally falls in love.

2nd March 2017, 12:00am

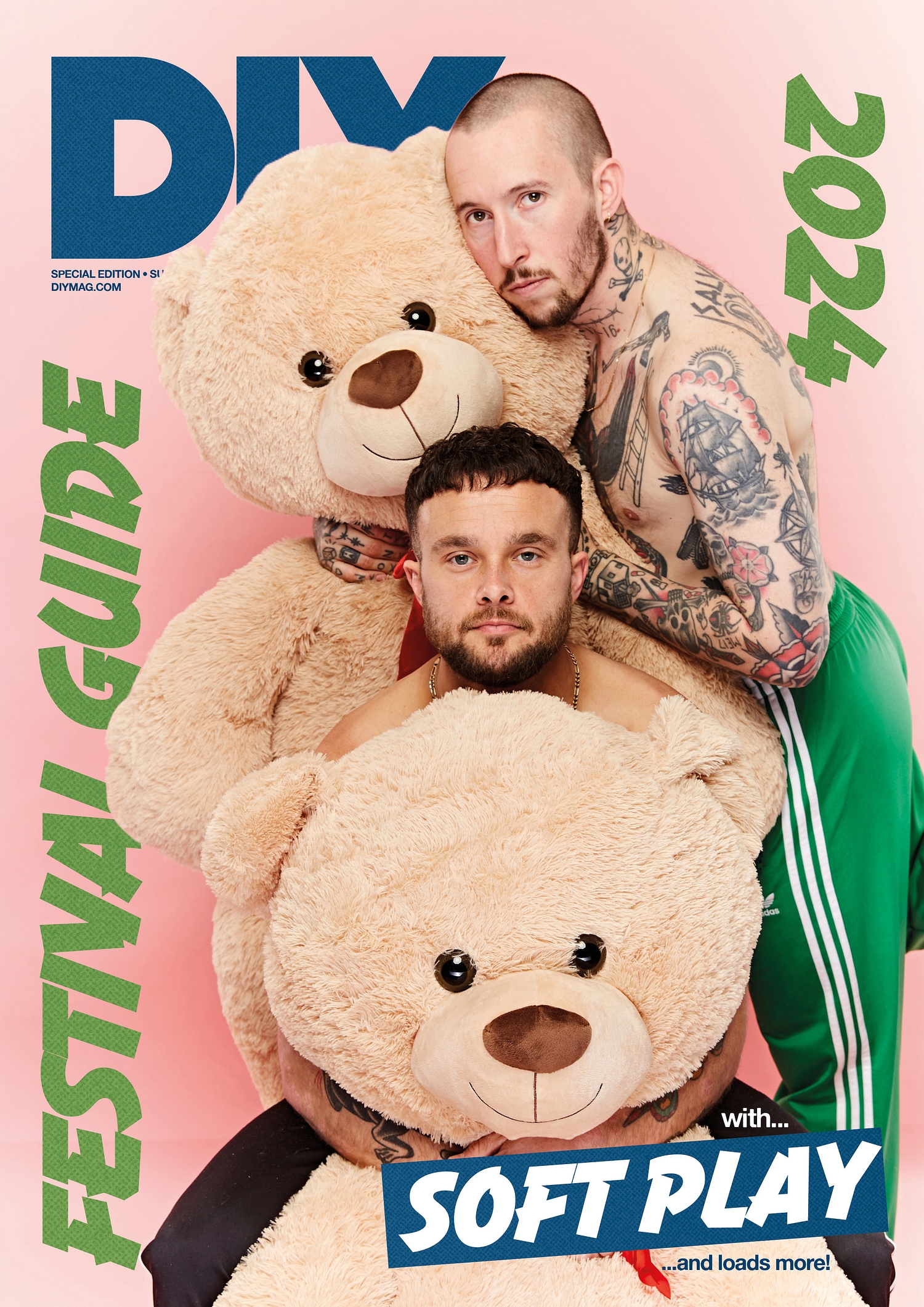

Featuring SOFT PLAY, Corinne Bailey Rae, 86TVs, English Teacher and more!