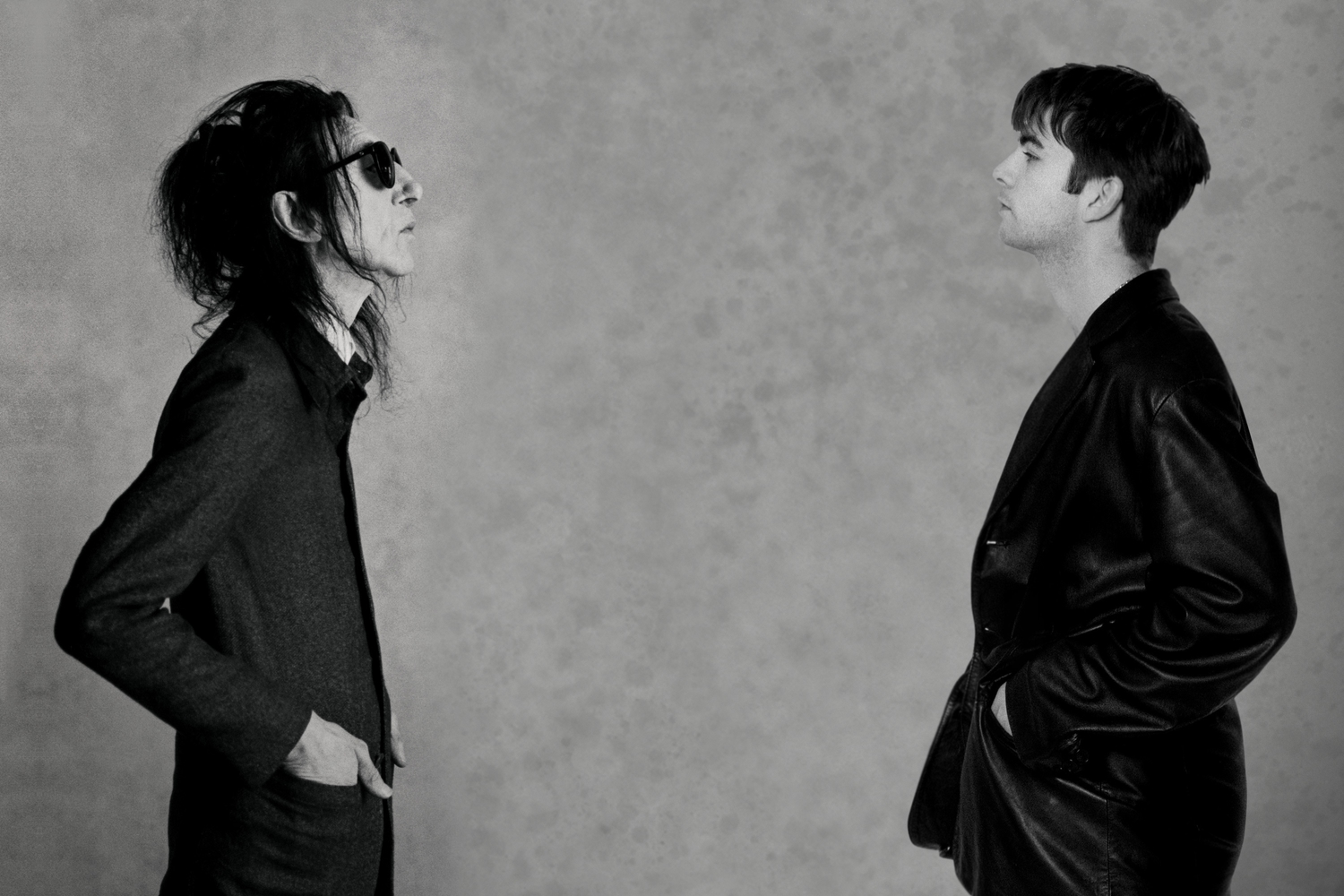

Interview Poetic License: John Cooper Clarke meets Fontaines DC’s Grian Chatten

One’s a stalwart of the scene, the punk poet of the people - the bard of Salford. One’s the eloquent singer of Ireland’s most literary-minded young chart-botherers. We’ll leave them to it…

Despite the four decades between them, Fontaines DC frontman Grian Chatten and longstanding punk poet John Cooper Clarke have much in common. For both of them, language is a living thing that constantly evolves, something to be heard, not read. Bringing the pair together over a scratchy three-way phone line today, they trade asides, quotes and one liners, eager to impress one another. On more than one occasion John threatens, tongue in cheek, to steal Grian’s material.

It’s partly because of figures like John, Grian says, that he thought he could make a career out of writing and performing in the first place. John, repaying the compliment, is full of admiration for Fontaines. Steadfastly refusing to invest in a computer or mobile phone, their material was played to him the night before our interview by his daughter, and he beams with the exuberance of the newly-converted.

John Cooper Clarke: If I might start this off, I’m a late convert to your work, Grian! I got hold of your stuff last night and I like your style, the overcoat, the look, the voice, these are all the ingredients to make great records. I hope you won’t be offended when I say there were echoes of the late Mark E. Smith, I mean I don’t mind when people compare me to Alexander Pope...

Grian Chatten, Fontaines DC: I never really get upset about that! He’s someone who never had any diminishing returns for me. I never got sick of his work.

Grian, when did you first hear John’s poetry?

Grian: I was probably 16 or 17, Carlos [O’Connell, guitarist] from the band showed me your appearance on a late-night chat show in the ‘80s. It was a similar appeal; it was the guttural energy. I have a sort of soft spot for the accent as well because I was born up in Cumbria, a town called Barrow-in-Furness. I can relate it to something that’s homely, and at the same time I can really feel the city and the ship-building town of Barrow. Not many accents can carry that spectrum of emotion.

John: I’d rather sound like you! I can’t believe I’ve still got this accent; I’ve been living in Essex for the last thirty years! I’m gonna have to get a refund from that elocution course I went on. The reason I won’t let go of my accent is that so many people have told me it’s part of my charm and, for me, the customer is always right!

Grian: When we played in Boston, because of the amount of reverence they have for Irish people there, I subconsciously ramped up my Irishness by about 20 percent.

In John’s new memoir, there’s a great passage about his early influences being Muhammed Ali and his mother’s Woman’s Own magazine. How do you think non-poetic figures and objects can influence your writing?

John: And my other big influence was Sir Peter O’Sullivan, the racing commentator in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, you can get albums of his famous races. And various menus and random lists.

Grian: I’ve got about four songs which are essentially just lists of lines I’ve written on a night out or something when I’ve had a few pints. I think they should really all be the beginnings of different songs, and I think I just get lazy and compile them all into one song.

John: What a great idea! There used to be a guy called Moondog, a street singer with a long white beard, he did a book called 100 First Lines. You’re in good company there, Grian. It’s very reassuring when that happens, I find.

Grian: When you say you hear echoes of different people in what I do, that’s why that doesn’t upset me.

“One of the main reasons I don’t think of poetry as an elitist pursuit anymore is because of people like John.”

— Grian Chatten

Can either of you remember the first time you wanted to be a writer?

Grian: I started writing songs when I was about nine years old. We were living in this bungalow in north County Dublin, about 30 miles outside of the city and I was trying to get my dad to buy me a pack of football stickers. He said if I learnt a poem and recited it to him off by heart, he’d buy me a pack. So I learned about 15 poems and managed to build the book. That sounds like it was just the rewards system, but it was also the fact that I felt like I was part of the poem. You go into a poem when you learn it off by heart, it becomes part of you.

John: Precisely! I’ll tell you when a poem’s dead: when it’s in a book. I mess about with poems night after night. I dismantle them, put them back together.

John, there’s a sequence in your book about a teacher who organised poetry competitions that were almost like rap battles…

John: It was a tough school. Put it this way, we had our own coroner! The teacher was Mr Malone, he was a tough guy. After the summer holiday he would always return to school with some fresh injury incurred in some daring outdoor pursuit. He had a glass eye, walked with a bit of a limp, a rugged outdoor type, but he also had this other side to his personality. He was in love with 19th-century poetry and he conveyed this enthusiasm to the rest of the class which became this hothouse of poetic activity. It was all very hormonal, a ‘my vocabulary’s bigger than his’ kind of thing. For the first time ever, I was enthusiastic about something and became good at it. From then on I thought I could make a living out of it. It’s funny you should mention your dad, Grian, because my dad discouraged this course of action at every opportunity. He’d say, ‘Name one famous poet that’s ever made a living out of it!’. He did it out of kindness really. He didn’t want to see me mugged off. But he gave me something to prove, like yours did.

Grian: I didn’t like poetry at school, we didn’t have a member of the education system to make it feel like it could be ours, we just had a woman whose voice was so dull that she rendered all the poems blank pages. We’d just sit there and the sound of the bell signalling the next class was the most poetic thing we heard all day. But you don’t have to look as far anymore for it not to seem like an elitist pursuit. I think one of the main reasons I don’t think of it as that anymore is because of people like John.

John, did you find any kindred spirits who’d come before you?

John: I used to live opposite a cinema called the Rialto, and they were showing the Roger Corman film The Fall of the House of Usher, starring Vincent Price. It scared the hell out of me, but I became interested in the work of Edgar Allan Poe. I went to the library and got everything Edgar Allan Poe had ever written, then I started reading about his life and I discovered that this poet, Charles Baudelaire had put his own work to one side to translate the entire canon of Edgar Allan Poe into French. Then I checked out Baudelaire, and discovered that he was very urban, a man about town with a fractured take on modern life as they would put it today. He was a modern guy, a city dweller, a bit louche, something to aspire to! The idea of becoming a citizen poet acquired this kind of glamour that we didn’t have an equivalent of in this country. But what we did have instead was the music hall. All these famous music hall guys were the superstars of their day and they specialised in monologues which blue collar people would pay cash money to witness. I felt, why not me?

In the past, Grian, you’ve spoken about how prolifically you were writing when working service industry jobs, and in John’s book you were constantly working by day and performing by night. Do either of you find inspiration from the working day?

John: The monotony of machinery is a big help. The sound of a printing machine has this really sexy syncopated shuffle beat that’s really helpful in the composition of poetry. That said I was still thinking, ‘I shouldn’t be living like this! I should be living at night!’. I did have a job punching out registration plates that drove me fucking crazy. You wouldn’t believe the decibel level.

Grian: I worked in this awful upmarket clothes shop where I had to sell sunglasses. I was overwhelmed with the knowledge that none of them were worth half of what they were being sold for. It was just the violent shelving of yourself. When you clock in in the morning, you’re really clocking out, do you know what I mean? I think the person that went missing for those eight hours rushed back in and I got a double dose of myself after. I used to work on receipt paper. It created a really nice sense of impermanence. John, when you’re talking about poems being a living thing and poems never being finished, I like having pockets full of scraps of paper that I’m never going to read again. I like when something really great is said in conversation and then never said again. That really excites me. It makes it feel like everything good is still in the future.

John: Very well put!

Grian: Both of those things made me develop my own style If I could call it that.

John: You’ve got the style alright, kid!

John Cooper Clarke’s memoir I Wanna Be Yours is out now via Picador. Fontaines DC’s ‘A Hero’s Death’ is out now via Partisan.

Read More

Fontaines DC’s UK & Ireland headline tour on sale now

The Irish quintet have just added new dates in London and Manchester too.

26th April 2024, 10:00am

Fontaines DC announce new album ‘ROMANCE’ & share lead single ‘Starburster’

The Irish quintet have also signed a new deal with XL Recordings.

17th April 2024, 6:32pm

Reading & Leeds welcome Fontaines DC, beabadoobee, Bleachers and more to 2024 lineup

Over fifty names are set to join R&L's six headline acts this August bank hols.

1st February 2024, 6:35pm

Sam Smith, Stormzy, Fontaines DC and more to play Sziget Festival 2024

The Island of Freedom have shared the first 35 names confirmed for next year's knees up in Hungary.

12th December 2023, 11:31am

With Bob Vylan, St Vincent, girl in red, Lizzy McAlpine and more.